Turning a former radio factory into a sixth-form film and television school proved a structural challenge for the project team, which created a central core of new media studios while refurbishing the surrounding building.

It’s not often that construction, teaching and cinema come together on a single project – but that is certainly the case with the new London Screen Academy in Highbury, north London. The building is still under construction but when complete it will become a new specialist sixth form-only free school for 1,000 16- to 19-year-olds, providing training in film and television, as well as a conventional educational curriculum.

The school is funded and run by the Department for Education (DfE) and developed by LocatED, the government-owned property company creating school places. LSA was created by a group of founders comprising top media names at Working Title, the creator of Four Weddings and a Funeral and Love Actually, Heyday Films, best known for Harry Potter, EON which is behind the James Bond films and one of the producers of the Last King of Scotland.

The building in question is Ladbroke House, a four-storey brick building a stone’s throw away from Arsenal football club’s Emirates ground. It was built in the 1930s as a factory facility for radio and television manufacturer AC Cossor, the first in fact to start selling TVs to the public and so a prophetic forerunner to the building’s future role. By 1937, the owners of Ladbroke House claimed that it was “the “largest self-contained radio factory in the British Empire.”

A company takeover after the Second World War saw the building sold to London Metropolitan University, under whose ownership it remained until it was bought by the government in 2012 with the initial intention of opening it as a secondary school. However this original plan, which was before the current founders came on board, came under local opposition and so it was decided a 16-19 college would be a better solution.

Reformatting

The building was structurally sound and the exterior was largely in reasonable condition apart from wear and tear; the decision was taken not to make external alterations because of sensitivity to local heritage. But there was a need for general repair and refurbishment, and internally reformatting was needed in order to adapt the building to its new use. Willmott Dixon Interiors was taken on as main contractor on the £26m job, which will be finished in time for the first students to arrive this September, with Architecture Initiative creating the designs and Price & Myers as structural engineer.

The conversion concept for the building is a relatively simple one. The building is roughly square in plan and was built with a steel frame with concrete beam and pot floor slabs. The building also has a basement partially surrounded by a shallow light well along the pavement above. External walls are non-loadbearing and clad in brickwork and before reconstruction the building primarily featured open-plan floors dotted with columns arranged into 6.3m x 6.3m bays.

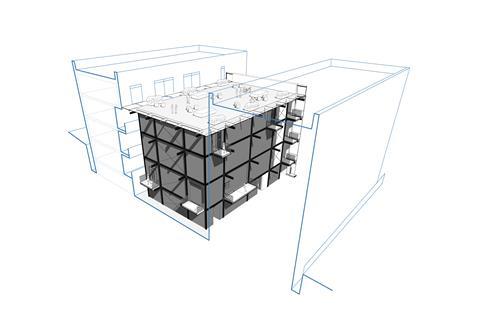

The concept sees the central section of the plan carved out on every floorplate to form a new U-shaped floorplan encircling a full-height void. The “U” segments of the plan are the width of two structural grid bays and are mainly divided into large cellular teaching rooms on each floor. But a new three-storey commercial-level film production studio is built in the central void section, surmounted by a rooftop terrace surrounded by the uppermost floor of the “U” section plan.

So the reconstruction project is essentially two projects rolled into one. The first involves the refurbishment of the “U” section areas. But the second – and most structurally challenging –project involves constructing what is, in structural terms at least, effectively a brand new building within the refurbished outer ring.

In order to do this the central section of each floorplate has been carefully demolished. Having a gigantic hole in the middle of a steel-frame building presents obvious problems with stability so a complex network of temporary props was constructed to support the retained structure while works were taking place.

New piling was then driven into the ground underneath the central section; luckily the relatively shallow mass-filled concrete pad foundations of the original building presented no obstruction to the positions of new piles and were easily removed.

Then began the intricate process of constructing the new studio structure floor by floor, which is still under way. As the steel framework for each new floor rises and is tied into the primary structure of the existing building, the secondary frame of temporary props is being removed.

Read more architectural reviews from Ike Ijeh, including:

The Cambridge Mosque

Bloomsbury Theatre, London

Xiqu Centre Opera House, Hong Kong

Fusing old to new

The process of tying in the new structure to the old one around it forms a crucial part of the engineering solution devised for the refurbished building. The edges of the existing floor slabs are supported by constructing a concrete ring beam on each floor. Once the ring beam is completed on each floor the temporary props can be removed and the process repeated on the floor above. A 1.9m-wide void separates the new steel structure from the concrete structure of the existing building so the new studio box will be clearly expressed as a separate element in the finished building. This also helps mitigate noise transference to the studio. A series of bridges connect the existing floor slabs to the studio. The existing structure and studio box are linked using a series of tie beams between both elements. This ensures the stability of the overall building by providing a stable core to the heavily deflected floor slabs.

So the new studio itself is essentially a giant triple-height steel frame box that uses concrete ring beams on every floor to tie into the existing structural frame around it. In order to minimise as far as possible the loads it exerts onto the surrounding building, its structural composition is relatively lightweight.

Despite the obvious and very exacting acoustic requirements a production studio surrounded by a school demands, the studio’s outer walls are only 220mm thick. As well as the steel frame, these walls comprise various layers of acoustic insulation including a wood wool acoustic finish to the outer face exposed to the surrounding school and quilted sound block insulation to the inner face.

Project Team

Client: Department for Education

Architect: Architecture Initiative

Main contractor: Willmott Dixon Interiors

Structural engineer: Price & Myers

Services engineer: WSP

Challenging

Willmott Dixon Interiors director of operations Tom McEvoy describes the logistics of effectively building within a building as arguably the most challenging aspect of the project. “We’re surrounded by roads on at least two sides and we share party walls with adjacent housing. Because it’s such a tight site there’s also no laydown area for any kind of storage or assembly during construction.

“Access is limited too, we had to form a hole in one of the basement light well walls and everything, including all the temporary steelworks, tower crane and piling rig had to come in and out of that.”

Of course the new production studio is only one half of the project; the rest has involved the extensive refurbishment of the original building that surrounds it. While the structural condition of its primary frame was generally good, there were some wear and tear problems associated with cracked lintels and corroded steel reinforcement helibars within concrete, all of which has now been repaired. The exterior brickwork has also been restored and repointed.

One of the biggest refurbishment challenges to the non-studio part of the project was the sagging and heavily deflected floors that were in the existing building. The beam-and-pot floor construction had been filled with terracotta void formers but over time this has sagged by up to 60mm across the full extent of the floor.

The solution was to pour a layer of leca aggregate chip onto deflected areas of the floor slab to then be covered with a polythene sheet and 25mm of new screed. Equally, the contractor made sure to attach any new fixings to the steel beams rather than the floor slab itself to prevent future deflection. But ultimately, the biggest measure used to do that is the new production studio itself which now acts a structurally stabilising core for the entire building.

The design theme for the refurbished interiors has been very much a light-industrial approach as Matt Goodwin, co-founder of the scheme’s architect, Architecture Initiative, explains. “We’ve stripped the building back to its structural frame and where possible left exposed brickwork and visible services on ceiling runners. We’ve also installed a new MVHR system and are installing new Crittall windows very much in keeping with the spirit of the original building and let a huge amount of light into floors that are sometimes up to 4m high.

“Where possible we’ve also kept original features but it’s a balancing act. Stair handrails, for instance, were way below regulation standards but rather than replacing them entirely we’re extending the railings upwards.”

The DfE is famous for the prescriptive specificity of its school building requirements, a constraint which is hard to reconcile with the unpredictability of refurbishment and conversion. But Goodwin maintains that by creating robust and hard-wearing surfaces and spaces that will be easier to maintain, the project has proved just as cost-effective as the more conventional standardised schools that DfE requirements are specifically designed to generate.

But happily there will be little that’s conventional about the London Screen Academy when it completes. By effectively creating a new building inside an old one, an old radio factory will have its media heritage renewed by structural creativity that, in the true spirit of film-making, remains firmly behind the scenes.

No comments yet