It may resemble a restoration project, but this 13th-century castle in France is being built from scratch entirely by hand, using medieval techniques, horse power and materials sourced from local quarries and forests

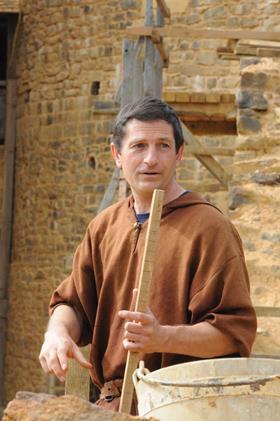

There can’t be many construction sites in the world where quarrymen hew rocks out of the ground with hammers and chisels, where builders wear woollen smocks, where measurements are taken in cubits, and where raw materials are moved around by horse and cart. But then Guédelon castle is no ordinary construction site.

Deep in a forest in northern Burgundy, just over 100 miles south of Paris, this is a building project like nothing else you’ll witness. Using only medieval construction methods and medieval-style tools, a team of 16 stonemasons, seven carpenters, four blacksmiths, three lumberjacks, three carters, a tiler, a potter and various other craftsmen and -women are building a 13th-century castle entirely by hand. No electric tools, no cranes and no lorries, with virtually all materials sourced on site.

But there’s another crucial difference between Guédelon and a modern construction site: here, visitors are encouraged to interact with the builders while they work. The growing castle attracts about 300,000 visitors a year, bringing in €5m annually, which finances the entire project.

Château de Guédelon and its surrounding site is owned by a private company, with chief executive Maryline Martin at the helm. “We call it experimental archeology,” she says of her mammoth project. “Essentially, that means we’re constructing a 13th-century castle in order to understand medieval building methods.” Or as the brochure states: “Guédelon sheds light on mysteries of the medieval world.”

Labour of love

It’s certainly a labour of love. Construction started way back in 1998 – the brainchild of Michel Guyot, the owner of a nearby renaissance castle – and probably won’t finish for another dozen or so years. So far, two of the exterior curtain walls are in place, as is the main hall, the chapel, the kitchen, the guardrooms, the bases of the four towers and some of the crenellated walkways that join them together. But there’s still plenty of work to complete on the gatehouse, the great tower and the portcullis.

Florian Renucci is Guédelon’s master mason, a medieval version of architect and project manager rolled into one. “We’re in the business of research,” he explains when asked why he and his colleagues were crazy enough to embark on such a punishing enterprise. “The goal is to find out what traditional architecture was like in the Middle Ages, before the industrial revolution. At the same time, we want to teach builders how to work with traditional tools and materials, and we want to show our visitors how it’s all done. So not only are we builders, but we’re archaeologists and teachers too.”

The site for this castle (some would say gargantuan folly) was chosen back in the mid-1990s, close to Michel Guyot’s existing castle. Most important was a quarry to provide clay for roof and floor tiles, sand for mortar and a massive 10,000m3 of sandstone for the castle walls. The 12ha of surrounding forest provides wood for the roof timbers and fuel to fire the kilns. The entire site was bought for 6,500 francs. (This was just before the introduction of the euro.)

Key to Guédelon’s authenticity is a committee of archaeologists, architects and historians who, throughout the project, have ensured the works remain true to the mid-1200s. Their research is based on existing buildings from the period, as well as medieval manuscripts, documents and even stained-glass windows.

Authenticity is something with which Maryline is rather obsessed. “At first, people didn’t understand what we were doing, and were even aggressive towards us,” she says. “They said we were cheating.” She describes how, in the early days, suspicious locals would spy on her workers from the surrounding forest, convinced that once the daily visitors had departed, power tools would appear from hiding places.

As the years passed, however, the critics came on side. They realised the techniques being employed were genuinely medieval: stone quarried by hammer and chisel; walls of outbuildings built of wattle and daub; terracotta roof tiles fired in kilns; ropes made of flax and hemp; hand-hewn roof beams.

The forerunner to the modern crane

On 13th-century building sites, the heaviest loads were lifted by a device known as a treadmill winch. A bit like a hamster wheel, it featured one or two vertical wheels on a central axis. Human operators would walk inside the wheels, hoisting loads of up to 600kg as they turned them. The winches could be dismantled and reassembled as the building progressed. Guédelon’s treadmill winches are identical to their medieval versions except for the modern pulleys, central axes and ropes, which comply with 21st-century healthy and safety regulations.

Downing tools for the winter

The castle’s 44 full-time construction workers are on site from March to November. They work long hours during the season and have paid time off over the winter, when frost makes it impossible to work with the non-hydraulic lime mortar. (There was no modern cement in the 13th century, of course.) All are paid substantially more than France’s minimum wage.

For anyone familiar with modern construction sites, Guédelon is a museum curiosity. Instead of roaring drills and angle grinders, there’s the gentle tapping of chisel on sandstone. Instead of lorry diesel fumes, there’s the whinnying of the three cart-horses, Paloma, Tyrolienne and Arpege.

“It’s a real pleasure, working here without noisy machines,” says Renucci. “It’s a luxury, not working with toxic products, dust, noise pollution and the fog of chemicals. I’m sure the Filipinos on Dubai construction sites don’t enjoy the same conditions we do.”

Baptiste Fabre is one of the project’s stonemasons. Trained in heritage restoration, he has worked at Guédelon for six years. Surely he occasionally gets frustrated at the glacial progress of the project, especially when he imagines electric tools achieving in 10 minutes what normally takes him 10 hours?

“I have a real sensibility for traditional techniques,” he says. “Between chiselling by hand and using an electric drill, I’d prefer to do it by hand, even if I worked on a modern building site. You can’t compare a traditional mason like me to a modern mason. They’re completely different fields. It’s like comparing a doctor of cardiology to a doctor of neurology. If you put me on a modern building site, I’d be completely lost.”

Despite all the medieval reenactment, Guédelon is still subject to modern construction regulations. There’s one telephone in the castle, for example – a legal requirement in case of emergency. The wooden scaffold poles are held with modern metal fixings. Some of the cordage, straps and pulleys on the winches are industrially produced. The workers may be dressed in smocks but, as Renucci explains, they have to wear steel-toecapped boots and hard hats (concealed beneath straw hats or a beige cloth). The masons require safety glasses.

Travelling 800 years back in time has posed many challenges for Renucci and his colleagues. The first, he explains, was psychological. “In construction, the automatic reflex nowadays is to order stuff online. We had to forget all about ordering materials or tools from China. That change of mindset took some doing.”

There were technical hurdles to overcome too. Lifting machinery includes anachronistic wooden devices such as hand-winches, capstans, sheer legs and treadmills (see “The forerunner to the modern crane”, page 39). Rain poses problems for the stonework, so workers had to be very canny with guttering and drainage.

To set the castle stones, they had to learn how to make and use the non-hydraulic lime mortar which, in the 21st century, is a complete anachronism. And the quarrymen had to learn how to read the colour of the sandstone before they started breaking it up to save themselves weeks of extra labour.

To fire the clay roof and floor tiles, tilers needed a working medieval kiln. “We went to London to see an old one in the British Museum,” Renucci remembers. Even then, they had to experiment many times to get the correct technique.

Twenty-one years into the build, however, and progress is smoother than ever. Maryline envisages the castle topping out around 2030. But after that there will be the interiors, the windows, furniture and furnishings to complete; all completed using medieval methods, of course. There’s even talk of building a medieval village and church, and a training centre for traditional construction techniques.

“I don’t think I’ll live to see the end of this project,” Maryline says, who is 59 years old. “We’re far from finishing our adventure.”

Dominic Bliss travelled to château de Guédelon courtesy of Burgundy Tourism. The castle, which is near a village called Moutiers-en-Puisaye, is open to the public from March to November.

No comments yet