On a vast regeneration site in London’s Wembley Park, developer Quintain is building what it hopes will be the UK’s largest build-to-rent scheme. Ike Ijeh went along to gauge the architectural and civic impact the private rented sector is having

In recent years the private rented sector (PRS) has become something of a Holy Grail. Large investors are piling into the sector because of the safe and predictable returns. Legal & General has big ambitions for PRS, investing and building with a pipeline of 3,000 homes, while private equity investor Sigma Capital is working with Keepmoat, Countryside Properties and Galliford Try on a £1bn investment into PRS. The government estimates that more than 80,000 PRS homes are either completed or planned, with the sector likely to grow to £70bn in value by 2022.

Essentially, the PRS is a professional version of the private rental market, which has proved so popular with small landlords. Residents can enter into short- or long-term tenancies with a professionally run organisation and enjoy purpose-built homes that come with communal facilities and on-site servicing and maintenance. Most people can see the value in diversifying the traditionally static UK housing market in an effort to help address the current crisis, so there has been much discussion about the revolutionary structural impact such schemes could have.

So far, nobody has seemed quite sure how to deliver PRS housing at the kind of scale that could make a meaningful difference to the supply and composition of the residential sector, but a new scheme in the shadow of Wembley stadium aims to do just that.

Alto is a new residential development of 362 flats arranged across four blocks. These range from nine to 19 storeys and have been designed by architecture practice Flanagan Lawrence for developer Quintain. They are part of Quintain’s massive £3bn Wembley Park masterplan, which involves 85 acres of formerly underdeveloped industrial land around the stadium being comprehensively regenerated, making it one of Europe’s largest regeneration projects.

Some 8.8 million ft² of mixed-use space is being built, which will include more than half a million square feet of retail space, a park, a school, a health centre, 42 acres of new public realm in the shape of streets, boulevards and squares, and more than 7,000 homes. The project is expected to fully complete by 2027.

Crucially, the Wembley Park masterplan also includes a significant commitment to PRS, with 5,000 of its homes being allocated to the sector, also known as “build to rent”. Already, 3,000 such properties are under construction, and they will be built and managed by Quintain, with leasing handled by a new rental company the developer has already set up.

The ambition is to create the UK’s largest purpose-built PRS development, with Quintain chief executive Angus Dodd identifying its benefits thus: “Our commitment to build to rent at Wembley Park means we can deliver the homes London needs far faster than if we were selling homes privately and ensures they will be occupied very shortly after they are complete.

“This long-term commitment also means we can design homes specifically for the needs of today’s generation of renters and provide fantastic shared facilities and professional management arrangements. We will ensure no apartment is left empty.”

Alto is therefore a microcosm of the wider residential demographic of the entire Wembley Park site. This is reflected in its accommodation mix: of its 362 flats, 211 are for private sale, 31 are affordable and 120 – just under one-third – are for the private rental sector.

So, architecturally, what differentiates a PRS scheme from any other residential development and what does Alto tell us about the kind of architectural, urban and civic impact the growing PRS sector might have?

Communal space

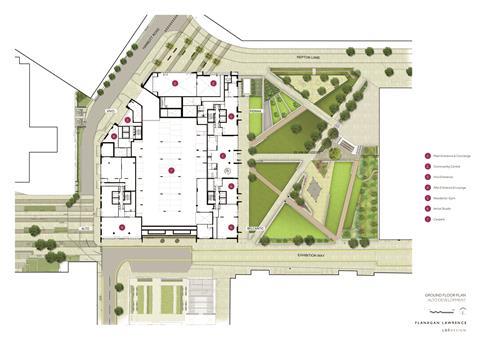

Externally, there is little to identify Alto as different from any other high-end contemporary residential building. It occupies one side of a new public garden and is split in two by a landscaped private courtyard raised to accommodate a shared car park underneath. Its elevation is expressed as paired stacks of prefabricated glass-fronted balconies framed by vertical fins that run the full height of the building. The fins and balconies are grouped into four-tiered shafts that reach progressively taller heights.

The effect is streamlined and minimalist and offers no clue as to the tenure of accommodation behind the facade. But the architecture does provide one significant clue as to the PRS agenda: the stepped tiers created by the different heights of each of the four shafts allow for the creation of communal gardens on the roof of the building. These correspond with the communal courtyard in the centre of the scheme and together underline how communal facilities are an essential ingredient of the build-to-rent sector.

These facilities become more evident on entering the building. A concierge lobby forms the main entrance for all residents but this leads to a sequence of shared spaces specifically designed for the PRS tenants. These include a large, shared modern kitchen filled with state-of-the-art appliances, a lounge bar, a residents’ club room, a gym, work areas and even a small cinema screening room.

“PRS generates all manner of communal uses,” explains the architect’s co-founder Jason Flanagan. “It can offer shared activities at ground and roof level and it constantly reinforces a sense of community and provides a social means for residents to interact.”

These activities can be useful in helping to occupy and animate what happens at the ground floor of blocks of flats, commonly the least attractive and lucrative residential floor level. Elsewhere on the ground floor Alto includes eight art studios and a 300m² community centre, all feeding into the pattern of communality established by the shared PRS facilities.

Alto is situated in a largely residential part of Wembley Park, but in busier, more public areas of the masterplan such as the square and boulevard, the PRS model is easily able to accommodate a more active mix of ground floor uses, which includes a combination of shops, bars and cafes that can be used by residents and non-residents alike. PRS therefore has the potential to enliven the street level in a way which traditional housing may find more difficult to achieve.

Within the PRS sector, the developer, or any lettings vehicle established to manage their units, is responsible for the long-term maintenance of communal areas. So this too tends to lead to the selection of robust and hard-wearing materials that will minimise ongoing maintenance costs. At Alto, this is channelled through a mixture of exposed poured and polished concrete finishes, tiled and wooden floors and in the entrance lobby, an elegant steel helical staircase.

Communal areas at Alto also feature wider corridors than similar market sale developments. This is a common feature of the PRS sector designed to accommodate the higher turnover of residents who need to move their furniture in and out of properties as a result of short tenancies.

For the same reason Alto’s cores have three lifts rather than the standard two that might be allocated for market sale cores, this enables one lift to effectively be used as a permanent residents’ ‘moving’ lift. In order to justify the presence of the additional lift, PRS cores tend to serve a larger number of flats than their market sale equivalents.

Blending in

Surprisingly perhaps, it is the flats themselves that exhibit the least differences between the PRS and private models. All Alto’s flats benefit from generous balconies and glazing and feature open-plan living spaces, but offer few clues as to which level of private tenure they belong.

As Quintain’s head of masterplanning and design Julian Tollast explains, this was a deliberate decision.

“It was about maintaining a consistent level of quality. PRS one- and two-bedroom flats might be slightly smaller than sale equivalents, while three-beds might occasionally be bigger. But in the main there’s little to set them apart.”

Allen does reveal one discreet difference between the tenures: in private flats, all services are handled individually, with meters, utilities and broadband modems located in the traditional manner in a store cupboard. But with PRS the equivalent cupboard is empty because these are centrally located in a communal area to enable easier access for maintenance.

So arguably in architectural terms, the biggest impact PRS may have may not be in the specifications of the residential units themselves but in communal circulation and communal ground-floor facilities. Alto proves that the sector clearly provides an opportunity for residential to animate the public realm in a new, innovative and engaging way.

But Alto also demonstrates the efficiencies available when PRS is strategically delivered across a vast masterplan site by one single developer capable of building and managing properties across an extensive integrated area. The next challenge will be delivering PRS on a piecemeal basis on pocket urban sites that are far smaller than Wembley Park and lack its centralised ownership, management and vision.

Project Team

Architect: Flanagan Lawrence

Client: Quintain

Main contractor: Wates

Structural engineer: Price & Myers

Services engineer: Hilson Moran

Quantity surveyor: TowerEight

Landscape architect: Lda

Project manager: Stace

No comments yet