The former House of Fraser store is just half a mile from the M&S flagship which the retailer controversially wants to knock down and rebuild. Thomas Lane meets the team to find out how they are making the refurbishment work

In November 2021 Westminster council granted planning for the redevelopment of two major department stores on London’s Oxford Street. The plans for the first, Marks & Spencer, involved demolishing three interlinked buildings and replacing them with one low mega mixed-use, low-energy scheme.

Plans for the second, the former House of Fraser half a mile to the east, were also for a mixed-use scheme with the difference being that most of the building’s existing structure and facade would be retained.

The M&S proposals proved highly controversial and became bogged down in one of Britain’s most high-profile and significant planning rows of recent years, which has still not been fully resolved. The row centres on the significantly higher upfront carbon emissions of demolition and rebuilding M&S coupled with the heritage value of the art deco Orchard House, the oldest of the three interlinked buildings.

Although unlisted, campaign group SAVE Britain’s Heritage argues that Orchard House is part of an ensemble of early five to six-storey 20th-century department stores that combine, in the words of architectural historian Pevsner, to produce the effect of a flotilla, sailing majestically along the street. Replacing this collection of buildings with one 10-storey, mega block would disrupt that urban grain.

Meanwhile, work is proceeding apace on the former House of Fraser store with completion scheduled for 2025. Are there any similarities between these two projects and does the latter have any lessons for the beleaguered M&S project team?

The biggest difference between the two projects is that the former House of Fraser is a single rectangular building with generous 90m x 40m floorplates occupying one city block, whereas M&S consists of three buildings on one site. The M&S site includes the 1930’s Orchard House on Oxford Street, which is conjoined with Neale House, built in 1986 to the west. The Orchard House extension is north of Orchard House and was built in the 1970s.

M&S argues that this arrangement is not fit for purpose, with a confusing layout and misaligned floors between the three buildings.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given they were both built in the 1930s, the six-storey Orchard House and the seven-storey former House of Fraser, which was originally DH Evans, share very similar features including Portland stone facades. Both are steel framed; Orchard House features a 7.3m grid whereas the latter has a 7.5m grid.

Despite M&S arguing that the floor-to-floor heights are below that of current standards, headroom in the former House of Fraser is slightly more constrained. Both buildings suffer from particularly tight floor-to-floor heights above the fifth floor.

Given that Orchard House is deemed unsuitable for refurbishment, how is the former House of Fraser being brought back into productive use?

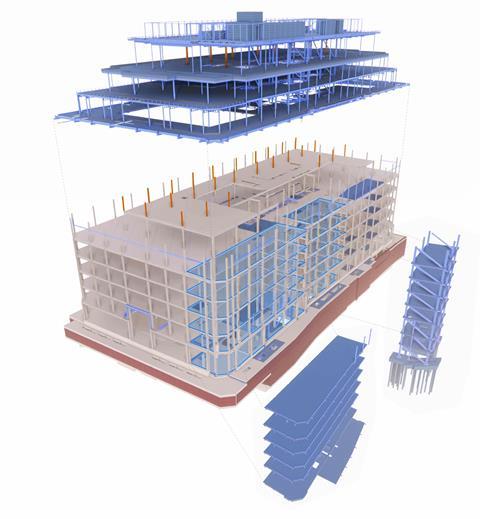

Developer Publica Properties is turning the store into a mixed-use scheme with retail at basement, ground and first-floor level with offices above. The building will include a gym with a swimming pool in the basement. Costing £132m, the architect is Studio PDP and the structural design is the responsibility of Civic Engineers.

“Fundamentally, this is a big, heavy, robust, good-quality building with a useable grid,” explains Simon Bennett, associate director at the engineer. “We talked to the client about demolishing and rebuilding it, we talked about facade retention. But, because it is a building of merit in a conservation area, complete demolition would probably have been challenging [from the planning perspective].

“We talked about a doughnut, where you keep the facade and the first bay of the structure to restrain the facade with a new building in the middle. This building has a really good structure, so our conclusion was: why would you demolish it as this is very wasteful?”

Not all the structure could be retained. The north-west corner was used for back-of-house purposes, including stock rooms and goods lifts. Bennett describes this as a “a warren of columns, walls and holes” and says once this was cleared out there was not much left, so the existing floors were taken out and new structure put in.

The walls in this corner provided the building with its lateral stability so this had to be replaced. The escalators serving all the floors were taken out leaving a void in the central section on the west side. Needing to be filled in, a braced steelwork core has been inserted to provide the missing stability and will be used as plantrooms on completion.

Bennett says the top two floors had very limited floor-to-ceiling heights. “These were not tenable for future use, so unfortunately we concluded they had to come off,” he says.

The building is being extended up by one floor; any more than this would have necessitated strengthening the columns down the building. “That costs a lot of time, money and carbon,” says Bennett.

Civic Engineers has done an upfront carbon calculation, which comes out at a commendable 103kgCO2/m2 for the structure. This figure incorporates the higher embodied carbon of 279 kgCO2/m2 of the new structural elements. If the whole building had been replaced, the upfront carbon of the structure would have been the same as those new structural elements, so refurbishment has saved nearly two-thirds of the carbon for the structure of a new building.

One of the challenges of repurposing old buildings is gaining an understanding of the structure. Bennett says a 1936 photograph of the DH Evans store under construction proved to be invaluable, as this showed building elements before these were covered up.

The image shows a lorry delivering a load of I section precast planks which were used for the floor slabs. It also shows a stack of stone mullions featuring a white dot on the ends which turned out to be a hole to accommodate a pin to hold these together once erected. “That is really useful to know when you are working on a building,” Bennett says.

A sign with the steelwork specialist’s name helped to establish the type of structural frame. “That allowed us to research the fabricator, which it turns out had a particular technology they were pushing at the time, which was solid circular steel columns, which is unusual for a building of this age and type.”

Contractor McLaren have been working on the building since 2022 and has stripped the building, including demolishing the roof slab and upper floors and the back-of-house elements in the north-west corner. The new steelwork is going up on the top of the building and a hole has been created for the basement swimming pool which had to be at least 20m long and 6m wide.

This has been shoehorned into a space between the column foundations. “Squeezing a pool into a building like this is really quite challenging,” observes Bennett.

The facade on the north-west corner has been retained using horizontal props connecting it to the existing structure which saved time, money and carbon compared to a conventional carbon retention system on the building exterior.

Up top, more structure has been retained than removing two floors would suggest as some of the columns have been reused. Only the perimeter of the fifth floor had restricted floor-to-ceiling heights as the building stepped above this – the central section of the fifth floor has been retained including the sixth-floor slab.

The seventh floor and roof slabs have been demolished but most of the columns supporting the seventh-floor slab have been kept and will be extended to create a deeper floorplate. The columns on the perimeter of the remaining section on the fifth floor were double height and are being moved to support the new roof slab over the eighth floor.

The original beams were concrete encased for fire protection with damaged concrete repaired where necessary. The lower flanges on the precast beams visible on the lorry in the 1936 photograph are damaged in places where the struts supporting the suspended ceiling have been removed.

According to Bennett, this is not a problem providing the rebar in precast beam centre is undamaged. “These floors have very little fire resistance, which is ironic as they were supplied by the Fireproof Floor Company,” he says.

The underside of the floors will be sprayed with thick fire-proofing material, which will help to fill in most of the holes. The circular columns will be protected with intumescent paint and left exposed.

The building was originally covered in protective netting because the facade was suspected of suffering from Regent’s Street disease as the spandrel panels had cracked. This is a condition where the steelwork supporting a stone facade has corroded, causing the stone to crack and fall off. An inspection revealed that the steelwork was in good condition, with cracks occurring next to the steel flanges of horizontal support beams at floor level.

The stone featured grooves to fit over the flanges, which are a weak point like those in a Kit-Kat bar. The team ascertained that the cracked stone fits behind the columns and mullions so cannot fall out.

These cracks were mostly too fine to allow water in and are not visible from the street, so very little work is needed. Some areas towards the top of the building are more exposed and the stonework thinner, and bigger cracks at this level will be filled with a lime mortar.

“The client’s previous advice had suggested that they needed to do an awful lot of work,” Bennett says. “Our approach has saved them several million pounds.”

The building is now at a stage where condition of the structure and facade is fully understood, with work advancing on its remediation and modification. So what are the lessons for the Marks & Spencer scheme?

Inevitably there will be some differences between Orchard House and the former House of Fraser, but these are likely to be minor, subject to the caveat that the condition of Orchard House is not fully understood.

“Buildings of this age in this location are generally pretty robust,” Bennett says. “There can be problems with Regent Street disease, with corrosion in some of the more exposed parts. But buildings of this age and type are very suitable for reuse.”

A stronger argument against retention is the fact that there are three buildings on the M&S site, complicating efforts to create a unified scheme. Another significant argument against retention is the extra development value created by increasing the height of the building.

Permission was granted for a 10-storey building before it was called in by Gove. This would increase the floor area by a substantial 71%. For comparison the floor area of the former House of Fraser will increase by less than 5%.

To date the arguments about retaining the existing buildings have centred on embodied carbon. M&S currently has permission to build a new 10-storey building on the site and – should Gove intervene again and successfully overturn this – the temptation will be for the M&S development team to submit a revised 10-storey scheme based around the existing buildings as to date building height has not been particularly controversial.

Extending Orchard House up by four floors is going to be difficult and carbon intensive and this may be true of the other two buildings on the site too. This suggests that any challenge by Gove on embodied carbon grounds should be considered in parallel with an increase in height too.

>> See also: What does the High Court’s ruling mean for M&S’s Oxford Street plans? Lawyers give their views

M&S won its legal challenge to Gove’s decision to block the scheme because there is no strong policy presumption in the NPPF in favour of repurposing buildings. Gove could revise the NPPF to incorporate such a policy and use this to overturn the High Court decision – but this will take time.

The most likely outcome is that the refurbished former House of Fraser, renamed The Elephant, will be finished and occupied while the arguments continue raging just up the road.

Reusing structural steel from Oxford Street on TBC London

Not all the structural steel has been reused on the former House of Fraser, notably beams from the demolished upper floors. Civic Engineers partner Gareth Atkinson was out on a bike ride with Basil Demeroutis, managing partner of Fore Partnership, who is developing Tower Bridge Court London by the eponymous bridge. They struck a deal to reuse 40 tonnes of steel from Oxford Street on the Tower Bridge scheme, now called TBC London.

At the time the former House of Fraser was being designed there was virtually no guidance on the reuse of structural steel. The Steel Construction Institute (SCI) published a protocol covering the reuse of post 1970s steel during the design development of the project but this was not much use on a building constructed in the 1930s, so the capacity of the steel has been established from engineering first principles.

As the TBC deal was being struck, the SCI extended the protocol to cover pre-1970s steel. “The steel for Tower Bridge was probably some of the first in the country to go through that process because at the point the deal was struck the pre-1970 steel guidance had only just been published,” Bennett says.

This covers rolled but not built up sections with additional strengthening plates rivetted or welded on. Only rolled sections from Oxford Street have been reused at Tower Bridge.

“Pushing that boundary, at that time would have been extremely challenging for the team at TBC,” Bennett says. Another reason for not reusing rivetted beams is the knobbly rivet heads make it difficult to integrate into a building.

Built up columns have been reused in new locations within Oxford Street for aesthetic reasons, with capacity established from engineering first principles. The steel was tested to determine its grade and weldability, its condition checked, then taken offsite to be fabricated for the new location. It will be tested again before being brought back to site for installation.

The general reuse of built up sections is some way off as in practice all steel placed on the UK market must be CE marked. CE marked steel must either conform to structural design Eurocodes or meet the SCI protocol, which rules out built up sections.

“This isn’t a problem in our case because the steel is not being placed on the market. It remains our client’s steel – they are just paying someone to do something to it,” Bennett explains.

“There is no practical reason why it shouldn’t be reused, it’s just a regulatory paper exercise. But on a practical level it does make reusing built up sections difficult. I imagine the industry will resolve this eventually. But we haven’t got there yet.”

Project team

Client Publica Properties

Architect Studio PDP

Structural engineer Civic Engineers

Services engineer ChapmanBDSP

Cost and project management MGAC

Contractor McLaren

No comments yet