Manchester United has an ambitous plan to rebuild Old Trafford within the same timescale. Everton has already done this and delivered its new, £760m stadium on budget and on time with careful planning and extensive use of MMC and digital tools, reports Thomas Lane

Notorious for going over budget and failing to complete on time, football stadium construction is a risky business. The Tottenham Hotspur stadium was the last big arena to complete in the UK. It was expected to cost £400m but ended up costing £1bn and was delivered seven months late, opening in 2019.

And the recriminations over the additional cost and delays of building the new Wembley stadium resulted in the largest lawsuit in UK construction history.

Everton has avoided this sad legacy, taking just five years from planning application to stadium handover. Admittedly, it spent 28 years thinking about how to increase the 39,572 capacity of Goodison Park and offer improved facilities. But staying at its home since 1892 was not an option as there was no space to expand. The ground is surrounded by homes and a school.

Everton eventually decided to build a new stadium two miles away from Goodison Park over Bramley Moore Dock beside the Mersey on land owned by Peel Holdings and leased to the club. Peel has big plans for a regeneration scheme called Liverpool Waters, which will be built to the south of the stadium. The idea is that the project will help to kickstart the bigger scheme.

Since the new stadium has completed, Sir Jim Ratcliffe, owner of rival Manchester United, has announced a £2bn Foster + Partners designed rebuild of Old Trafford. Ratcliffe wants to build the new stadium within five years by floating large modular components down the Mersey and Manchester Ship Canal. Given that Everton’s timescale matches United’s, and the stadium was built largely out of modular components, there could be valuable lessons for Ratcliffe and co – provided they can stomach borrowing ideas from a Liverpool club.

So, how did the team behind the new Everton stadium successfully deliver it on time? And what it is like? Building went along to take a look.

What is the new stadium like?

After 132 years at Goodison Park, Everton FC is gearing up to start the 2024-25 season at a brand new, 52,888-seat stadium built over a former dock next to the Mersey. The building is finished and the club is currently running test events to make sure that everything runs smoothly once the season starts in August.

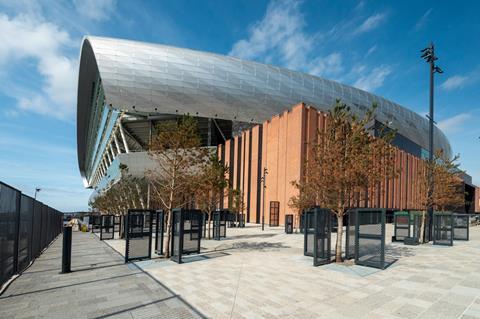

Located in the northern dock complex at the far end of Liverpool Waterfront, much of the area is wasteland punctuated by the odd derelict warehouse. Although the stadium stands out as there are no buildings of comparable height nearby, much of it is obscured by the high dock wall that runs the length of Regent Road.

The shiny, curved perforated metal roof wrapping around the upper part of the stadium and the glazed southern end is clearly visible from the road but it is only once you pass through one of the openings punched into the listed dock wall that it becomes apparent that the building is a game of two halves; the curvaceous, contemporary upper half sits on a traditional-looking rectangular brick box.

Intended to reference the brick-built warehouses nearby – including Stanley Dock Tobacco warehouse, the largest brick warehouse in the world down the road – it is unfortunate that the old buildings are hidden by the dock wall. The neighbouring water treatment plant is the most obvious reference as it is almost identical in terms of height, shape and scale to the stadium’s brick base.

There is a large plaza between the wall and the stadium with historic dockside elements including granite cobbles, railway lines and mooring bollards carefully reinstated. There is also a distinctive blue bollard erected in memory of Michael Jones, the site worker and Everton fan who died during the stadium’s construction.

The standard paving changes to a blue flecked stone which references the former dock over which the stadium is built with the large granite dockside blocks still clearly visible. Somewhat counter-intuitively, the building is perpendicular to the dock as orientating it in the same direction was impossible because it would have meant piling through listed structure. The north-south orientation is better for light distribution too, and this created the space for the large plaza.

A former hydraulic engine house, the only historic building on the site, has been carefully restored.

The south side of the stadium, which houses the home stand, is close to the neighbouring dock edge called Everton Way. It features 36,000 embedded, engraved blocks celebrating the births, marriages and deaths of Evertonians.

The west side faces the Mersey and Irish Sea and features an external terrace, where fan can sit and enjoy the views or watch the players arriving and entering the building through a tunnel in the terrace. Part of Bramley Moore Dock has been retained on this side as it connects the river to the docks south of this point.

The distinctive truss design used by architect Archibald Leitch for the balustrades on the Bullens Road stand at Goodison Park is referenced here at every opportunity – in the dockside balustrades, the sides of the precast benches in the plaza and rather too subtly in the arrangement of coloured bricks used for the stadium sides.

Walk through the players’ tunnel into the stadium and you are greeted by an ocean of blue seating. Hard up against the pitch, this is steeply raked to keep everyone close to the action, with the rake just 0.1° below the maximum 35°allowed for stadium bowls.

As expected in modern stadiums, there are large screens at the south and north ends so that spectators can see replays and close-ups of the action while the overhanging roof keeps everyone dry.

There are different categories of seating – basic plastic seats, padded blue seats and, in a European football stadium first, reclining seats which aim to offer an experience akin to premier cinema seating.

There is a selection of restaurants including Beyond, which is adjacent to the players’ tunnel and features one-way glass. Access to these restaurants comes as part of a range of membership packages, all of which are now sold out.

Other fans will have to content themselves with the food and drink outlets on the concourses, where burgers, salt and pepper fried chicken and the infamous “toffee doughnut” covered in blue icing and thick cream are available. The south stand also features a glazed area offering views over the Mersey and the city to the south.

Two test events have been held to date with very positive feedback from fans, press and the design team. Architect Dan Meis went to the second test event on 23 March and was delighted by the experience. “I’ve been doing this a long time, and I’ve never had a situation where I felt part of the fans. To have people grab me and take selfies with their kids is not something architects get as they are rarely recognized. To see the look on the faces of the fans was priceless and an amazing experience.”

Designing the stadium

The stadium was designed by Dan Meis, an American architect who has designed stadiums all over the world. Although fans were supportive of the move from Goodison Park providing the stadium remained within the city boundaries, it was important to keep them onside by making sure that the new building met or surpassed their expectations.

For Meis, who had never previously designed a stadium in the UK – and who was acutely aware of being an American architect working in a northern English town – retaining the quality of a live English football experience in the new building was a primary goal. “Stadiums grow up over time,” he explains.

“There was a pitch and a stand, and then, as the club grew, another stand. And then another architect and engineer did another stand. They grow up in these quirky and unusual ways, which brings a lot of the charm and the uniqueness to the buildings.”

He adds that, as stadiums are engineering led, much of the visual experience enjoyed by fans is structural, a quality exploited by Foster + Partners and Mott MacDonald to the full with the Wembley arch.

Meis wanted to introduce that quirkiness and variety into the building but says Bill Kenwright, the club chair at the time, “hated” the idea because it seemed old fashioned. Instead Meis has made each of the four stands facing the pitch subtly different, even though the concept will probably escape most visitors. Instead, the Archibald Leitch decorative truss motif repeats throughout the project.

The long history of Everton and the fact that it is a very local, family-focused team with members stretching back for generations, meant the design had to put the fans first. “That is what is unique compared to a lot of buildings I’ve done over the years which are so revenue driven,” Meis says. “This will always be different from any other project I have ever done because the club was so clear that it had to be a fan-driven design.”

Meis and Everton agreed that the stadium had to be a “cauldron of energy with a bear-pit atmosphere” on match days. In practical terms this means keeping the spectators, and therefore the stands, as close as possible to the pitch, something that Meis says has been compromised in most stadiums.

“The push for buildings to become more multi-purpose and international are the things that tend to drive the stands away from the pitch to make them more flexible and able to switch to an NFL [American National Football League] field, or putting in more commercial elements into the building.

“The more that you can simplify the seating and keep the stands very steep and right on top of the goals and sidelines, the better. That’s unique to the traditional, English football ground. And I think that’s the real magic that we can capture, even if it is in a big, shiny new building.”

The local nature of Everton’s supporter base and its location within a northern city was also a benefit as there was less pressure to stuff the stadium full of corporate boxes which take up a lot of space and separate the bowl into several levels. Everton does have corporate facilities, but these are limited to one level just on the east and west stands.

Where did the distinctive juxtaposition of a brick box topped by the shiny metal curved roof come from? Meis wanted to reference the local brick warehouses but was wary of pastiche so introduced a contemporary looking roof.

“One of my very first sketches of Bramley Moore was a scribble of brick with this kind of wave coming over it. I love that idea of it feeling like this had just grown out of the docks next to the Mersey – and that the roof was breaking out of the brick in the way a wave washes over a wall.”

Meis says Kenwright liked the idea of combining the more traditional base with a contemporary roof, and the rest of the team agreed that this was the way to go.

The technical design was handled by specialist stadium architect Pattern Design, which was bought by BDP in 2021. Now called BDP Pattern, they suggested replacing a planned multi-storey car park on the west side, which was intended to shelter the stadium from the wind coming off the Irish Sea, with external terracing.

“This has two benefits,” explains Jon-Scott Kohli, the architect director of BDP Pattern. “One, it gets people up quite high so that they can see over the river wall and enjoy beautiful panoramic views down the river Mersey. It has also created a new public space, and we hope that there will be some events as part of Liverpool’s public space programme.”

A hiccup during planning was the English Heritage objection to filling in the dock, with UNESCO threatening to pull the waterfront’s World Heritage Site status too. This objection placed the project into the hands of the government.

“Because Historic England had objected, it was referred to the secretary of state,” Kohli says. “The secretary of state at the time [Robert Jenrick] decided not to call in the scheme to review, but allowed the local planning permission to stand. And then, in reaction, UNESCO pulled the World Heritage Site status.”

Kholi says that Historic England was closely involved with the project during construction. The building structure straddles the listed dock walls so these could be reinstated at some point in the future. It was also involved in detailed design decisions.

“[Historic England was involved in] everything from the selection of the bricks on the facade to the strategy by which historic artefacts were found, catalogued, repaired and reinstated on the site.”

Construction

The stadium has been built by Laing O’Rourke in 178 weeks under a design and build lump sum contract as, unlike Spurs, who built their stadium using construction management, Everton did not want to take the risk on the job.

For project director Gareth Jacques, one of the biggest risks was the location. With clear views over the Irish Sea, wind was a big problem.

Jacques says the assumption was that the cranes would not be able to handle lifts over 50 metres 40% of the time. The dock wall next to the stadium is listed, so materials had to be taken through a small gap. Jacques did consider bringing materials in by boat, but ruled this out because of the tidal range of up to nine metres and strong current.

The answer was prefabrication and modular construction. “We developed what we called a ground zero construction philosophy where we could prefabricate large sections of the stadium, particularly the roof steelwork at ground level when it was too windy to lift. Then, when the weather was good, we really concentrated on lifting critical path components,” Jacques says.

Another consideration was labour availability. “At peak we were up to 1,300 people on site daily. We calculated that, if we hadn’t adopted all the DfMA and MMC, we probably would have needed nearly 3,000 people.”

Careful planning including a fully digital design and construction process was essential to leverage the maximum benefits of DfMA and hit the completion deadline. This included fixing 42% of the precast design and starting manufacture before taking possession of the site.

The speed of the programme even meant that Laing O’Rourke had to outsource manufacture of the precast terracing units to Banagher in Northern Ireland as its Explore factory – now known as Centre of Excellence for Modern Construction (CMC) – was at full capacity.

“The scale of the DfMA and MMC at Everton was such that it was too much for CMC as a standalone facility, particularly bearing in mind our other projects at the time and because the programme was so fast,” Jacques explains.

The team hit the ground running. “On day one we had our first welfare unit, our first cabins, our site set up and, within the first week, we made a start on contract scope,” Jacques says.

The first job was to survey and clear out the dock, particularly as the docks were a target for the Luftwaffe in the Second World War with the risk of unexploded ordnance. A team of divers worked 24/7 to survey the dock and found 12 unexploded artillery shells, which were removed by the Navy and detonated off site.

“It was a frustrating time because it’s quite slow work,” Jacques says. “We were doing a 24/7 shift because we couldn’t really progress with the superstructure until we had filled the dock. But, ultimately, we were vindicated in that thoroughness because, if we had hit one of those [shells] with a piling rig, it would have been a big problem.”

The next job was to fill in the dock with sand, a job undertaken by Dutch dredging specialist Boskalis whose skills extend to refloating the Ever Given container vessel which ran aground and blocked the Suez Canal in 2021 for six days. The specialist nature of Boskalis meant they had to be booked well in advance, before planning was even granted.

The Boskalis dredger scooped up 3,500 cubic metres of sand at a time 20 nautical miles out in the Irish Sea and brought it to shore, where it was mixed in a 5:1 ratio of water to sand so it could be pumped into the dock. When the dock had been filled in, the sand was compacted with a 19-tonne hammer and more sand added as it settled.

Jacques describes the sand infill as an “elaborate temporary works solution” as its main function was to provide a base for the piling rigs. The sand does also have one crucial permanent role as it supports the pitch.

The first piece of twin wall superstructure, which was used for the cores on each corner of the stadium, was installed less than six months after taking possession of the site. With the cores 80% complete, work started on the steelwork used for the more lightly loaded north and south stands, with precast used for the east and west.

Starting on the steelwork was an important milestone for Jacques. “Driving the start date for the steel frame was really important as it meant ensuring the site was ready and the product was available in sufficient quantities to suit the programme outputs,” he says.

“Once we started, the steel frame the programme just exploded because we continued with the precast concrete too. We were lifting up to 60 pieces per day with four tower cranes and up to 20 mobiles.”

Laing O’Rourke pioneered the use of what Jacques describes as “twin step” precast terracing. These are 10m long sections of terrace that incorporate two seating steps rather than the usual one, which has the benefit of fewer lifts and a reduced number of joints that need to be sealed.

“It reduces the amount of lifting and dependency on good weather for the lift,” Jacques explains. “It’s also safer because you’ve got less people working at height.

“And a nice, nuanced byproduct of this solution was that, when you are building a football stadium bowl, the mastic contractor tends to be on the critical path for quite a long time. Until you get relatively weathertight and dry, you don’t want to start too much of the fit out underneath the terracing units.”

The roof structure is supported by five large trusses which were built from components on the ground, then lifted into position in three large sections and bolted together in good weather.

The base of the stadium below the roof includes 650,000 bricks. Jacques calculates that 100 bricklayers would have been needed to meet the programme.

Instead, handmade bricks, which were cut in half, were fixed by bricklayers in the factory onto precast panels and fixed into position by a team of four people armed with a cherry picker and small crane. A total of 730 panels was needed, of which just one was rejected thanks to a virtual reality quality assurance tool used in the factory.

Even the standing seam roof managed to incorporate a first. A roll of aluminum sheet was formed into standing seam sections at roof level. Everton features the longest ever rolled in the UK at 172m long.

Jacques explains the advantages: “It is safer and easier for the team and has fewer joints. There is less risk of failure and latent defects through the system.”

The bespoke perforated barrel cladding was installed in 872 pieces. The project needed 914 toilets, which were manufactured and tested as complete units incorporating the pan, frame, back wall, cistern and pipework in the factory. These have helped to take the total percentage of DfMA components in the completed building up to 75%, which was a big factor in enabling Laing O’Rourke to hand over the project one day early.

Five lessons for Manchester United’s new stadium plans

Make a rock solid case for planning

The biggest planning challenge faced by Everton was UNESCO’s threat to withdraw Liverpool Waterfront’s World Heritage Site status. Alix Waldron, Everton’s director of new stadium development, says that UNESCO and Historic England were always going to object to the dock being filled in. She says Everton kept them engaged throughout the design process, so they didn’t object to the stadium design.

Waldron says that Everton also carried out what she believes is one of the largest ever public consultation exercises, with over 60,000 responses over two phases. The first asked about the principle of the project and the second the design and transport aspects.

She says that people were over 90% supportive in response to almost every question in the consultation. Liverpool City Council was supportive, but there was always a risk of the project being called in by the government.

“We knew that it had to be absolutely perfect because of the risk of being called in to central government – which it was,” Waldron explains.” It was referred after approval from the local authority, but the government decided not to intervene because we have been so thorough in the engagement and planning process.”

Early contractor engagement

Careful planning was crucial for timely delivery of the project, something which could only be achieved by a long lead-in time with the contractor. Laing O’Rourke was engaged under a preconstruction services agreement (PCSA).

Jacques explains: “One of the real benefits at Everton was that we had a healthy PCSA period, so we were very aligned with the club with the message that you get more certainty and consistency if we start a bit later, but build extremely efficiently once we start. It gave us time to work out the design, the engineering solutions, minimise the impact of risk, and develop the 4D model.

“We had built the stadium twice in the 4D virtual space before we took possession of the site. Could it [Old Trafford] be done in five years? Yes, it could. But you’re not going to do it in five years with a six-month pre-construction period. I would say you need two years.”

Digital planning and construction

Everton stadium was digitally planned from start to finish and included designing components for manufacture, logistics and modelling how the stadium was built. Site workers were armed with tablets rather than drawings.

A key innovation at Everton was a virtual reality room with a digital Gant chart on one wall, a federated 3D model with specialist contractor input, logistics and site layout on the third wall. Change the date on the Gant chart and the other walls change to reflect what is meant to be happening at that specific time.

“We can look ahead one week, a day, three months, six months, eight months and it changes the model immediately,” Jacques says. “This process flagged two major sequencing issues which my senior team and I were convinced that we wouldn’t have noticed if we had been using our traditional planning methods.

“And, because it flagged it five, six months in advance, we were able to change the sequencing in good time and communicate the new programme with the team who carried it out on site without a hitch.”

Modular construction

Ratcliffe says floating large modular components down the Manchester Ship Canal will be key to Old Trafford being built within five years. DfMA and prefabrication was critical to Everton’s fast build programme, but Jacques cautions that large components must be combined with smaller elements.

“The Everton approach combined with some large modular components would probably be the right answer because, while we used a lot of modular, we used small modular pieces which gave us multiple work faces so we could always always achieve productivity and output.

“If everything is large modular, there is a risk of having downtime if there is a problem with any part of it.”

Collaboration

People working on successful projects nearly always cite good teamwork as a key reason – and Everton is no exception, as BDP Pattern’s Jon-Scott Kohli explains. “That this project was delivered as smoothly and successfully as it was is a testament to the teamwork,” he says.

“It requires people to buy into an idea about what we are trying to achieve and putting the project first. The club did a very good job of choosing a contractor and design team that really shared their values with a strategic plan about the principles that they wanted to see in the project.

“And also trusting their design project team to offer the right solution. That kind of collaboration is absolutely crucial in a in a project like this.”

Project team

Client Everton Stadium Development

Concept architect Meis Architects

Executive architect BDP Pattern

Structural, MEP and civils engineer Buro Happold

Cost consultant RLB

Project manager Gardiner & Theobald

Landscape architect Planit-IE

Main contractor Laing O’Rourke

Dock infill Boskalis

Piling Expanded

Steelwork Severfield

Precast concrete Banagher

Brickwork Vetter

MEP installation Crown House

Roof cladding Lindner Prater

No comments yet