The distinctive sloping roof of 70 St Mary Axe has earned it the nickname ‘The Can of Ham’. But to fulfil the demands of the build programme – and the client – contractor Mace has had to adopt ultra-efficient methods that think outside the box. Photography by James Reid

‘We’ve got to get the quality absolutely precise.” It’s a mantra Nick Moore chants repeatedly on our tour of 70 St Mary Axe, a 21-storey office tower currently under construction in the City of London. Moore is a director of Mace, the contractor responsible for building the curvaceous scheme which, even before completion of its construction, has acquired the moniker of “The Can of Ham”.

Moore’s focus on construction quality is, one suspects, at least in part due to the unrelenting scrutiny of the design and construction process by the project’s client, the inimitable Geoff Harris, head of development at TH Real Estate. “Geoff is quite a character; he’s very, very particular about how he wants this job to look when it’s finished, which is great,” Moore says. “Over the years I’ve worked with lots of clients, many of whom don’t take much interest in a project until it’s almost built and then they turn up on site and say ‘I didn’t think it was going to look like that’; that won’t happen here because Geoff knows what he wants.” (Harris is, in fact, such a frequent visitor to the construction site that he even has his own PPE locker in Mace’s site hut.)

The elegantly tapered building Harris has tasked Mace to build will house 28,000m2 of premium office space set over 21 floors. The building’s unique shape means that each office floor is a slightly different size from the ones above and below it, but all benefit from views out through the building’s glazed exterior. The building’s shape and its City location mean that this is proving to be a demanding building to construct. “This scheme has challenges you wouldn’t get on a standard building,” explains Moore. And the story of how those challenges are being met is equally distinctive.

State of play

To Moore’s credit, construction is actually slightly ahead of programme. Standing in the double-height space that will, within a year, form the building’s reception area, Moore outlines the current state of play: “Construction of the building’s concrete core is complete, its steel frame has reached level 22, corrugated steel floor decking is being installed on level 17, the floors are being concreted on level 15 and the cladding has started to be installed on level 7,” he says. “We’re ahead of programme, but not as far ahead as I’d like us to be,” he adds.

It is, perhaps, no surprise that the project is progressing well because, even at 5pm on a cold, dark winter’s evening, under the glare of the site’s artificial lights, the clatter of activity shows no sign of abating. “Normally we work till about 9pm, but tonight the steelwork guys will put in a late shift to finish off a level because it is forecast to be windy for the next few days so it’s unlikely that they’ll be able to work for the rest of the week,” Moore explains.

While standing in the reception area, Moore uses the opportunity to show how the precast concrete fins will be attached to the building’s core and concrete ribs onto the underside of the soffit to line up precisely with the cladding supports. “If these are positioned just half a centimetre out, then you will see it,” explains Moore. “That’s why the setting-out of the cladding, positioning of core, setting-out of steelwork – everything, in fact – has to be spot on.”

One of the more unusual aspects of this project is that, because of the building’s shape, cladding installation has had to start on the ground floor on both the north and the south elevations. These are the elevations that curve outwards and then in again, to meet in the arch forming the building’s roof. “Because of the shape of the building we’ve had to clad progressively up from the ground floor on the north and south elevations because if we’d started the install at level 2, we would not have been able to fit the ground floor cladding,” Moore explains. “All of the vertical ribs have to be aligned exactly, which is why we are so concerned about accuracy.”

The cladding on these elevations is formed from a double skin of cold-curved laminated glass, which is held in place by a precisely curved aluminium frame. The unitised panels are brought to site in 1.5m-wide by 3.8m-high (storey height) modules for installation by Focchi, the cladding package contractor.

“Geoff had a casting vote on the choice of most subcontractors,” says Moore.

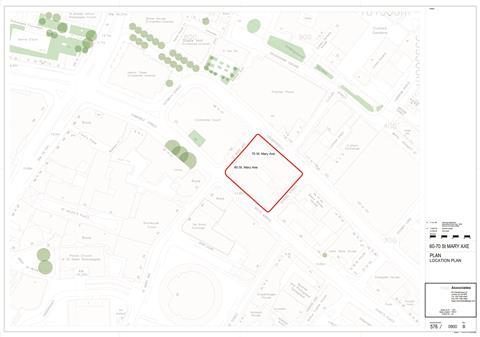

Cladding installation is more flexible on the east and west elevations, where flat glazed modules will be fitted. As a consequence, Mace is able to keep the ground floor temporarily free of cladding on these elevations to maintain access to the building for both personnel and materials. The materials and personnel hoists are located on the Goring Street elevation (see plan, right) to provide access to the floor plates.

All the building’s floorplates are column-free. Cellular beams span the 12m from the concrete core to the faceted steel columns incorporated into the building’s curved facade. To give the building its curved, organic appearance, these raking columns will be fitted with a curved, anodised aluminium skin to integrate it with the curved facade glazing.

On the level 3 floorplate, the positioning targets are still visible on the raking steels forming the perimeter columns. “The steelwork’s position is checked against co-ordinates at every level to ensure it’s within tolerance, because if it were to twist or go out of tolerance then physically you would not be able to fit the cladding to the building,” explains Moore. “It’s all about precision: the steel has to be right because once we’ve concreted it into the floor deck then that’s it,” he adds, repeating his mantra.

The concrete floor slabs have been spray-painted in a patchwork of colours that define which areas are allocated to storage and access; the painting has ensured a clutter-free corridor around the floor’s perimeter to allow cladding installation. “We have to keep the building as clean and neat as possible – if not, Mr Harris will be on us like a tonne of bricks,” laughs Moore.

Each floor incorporates what Moore describes as a “generously sized” lift lobby formed by the building’s core: “That’s what Geoff wants and that’s what he’s going to get,” says Moore.

Service risers run up through the core. Many of the services have already been installed. The services were delivered to site as prefabricated modules and lowered down the riser for connection by services contractor Mace MEP. The modules incorporate a checker-plate platform where they pass through each floorplate to close off the riser.

The cores will also incorporate the office toilets. These will be fitted out using a prefabricated solution, the components of which are currently being fabricated in Scotland for delivery to site as flat-packed units. It is a solution intended to deliver a high-quality finish by harnessing the efficiency and accuracy of off-site manufacture.

While the steel structure races upwards, Moore is hurrying to complete work in the building’s three basement levels. The basement is home to the plant that was too heavy to be installed in the roof-level plant room, such as the domestic water and sprinkler storage tanks, electrical distribution boards, and huge oil tanks to fuel the standby generators. The oil tanks are so large they had to be craned into position in basement level 2 before the level 3 slab was constructed above it.

The chiller plant is being installed by craning it in through holes strategically left in the floor slabs above. In preparation, the floor was painted and the services fitted to the soffit above the chillers. The basement also includes 35 showers to cater for cyclists using the building’s 360 bicycle parking spaces. “I want to get the basement areas completed by June so that I can shut it off from the site,” says Moore.

There is still plenty of work to be done: the landlord’s specification is for the scheme to be shell, core and floor; Mace has yet to start installation of the raised access floor. There are also three floors, which will be fitted out to Category A, each with a different style, for use by TH Real Estate to market the scheme.

Getting down and dirty

Work started on site in April 2015, when Keltbray demolished the two buildings that occupied the plot. Mace started on site in June the following year. One of the first tasks was constructing ramps down to the existing basement slab to provide ground-level access for the piling rigs to install the building’s 50 piles through holes made in the slab.

At the same time as the piles were being bored, a secant piled wall was installed around the site’s perimeter. The basement of the new building is a lot deeper than the existing basement; its excavation required the walls to be propped until the new floor slabs were cast. The basement was dug by breaking out the existing slab and then digging down.

As soon as the excavations had reached the required depth, the piles were cropped and Mace constructed the building’s raft foundation. The slipform rig was then launched to construct the building’s core.

Slipform (as opposed to jump-form) construction was used for its speed. To ensure the core was constructed accurately, concrete contractor Morrisroe prefabricated the slipform rig off site, for assembly on site from large prefabricated sections.

The core contains lift shafts, staircases, risers and toilets. “It’s a big piece of construction to do as a slipform,” says Moore.

The rig climbed between 2m and 2.5m of elevation per day. As with all aspects of this project, accuracy of construction was paramount, and the core was continuously monitored using optical plumbs to ensure it was in precisely the right place. “We were looking for Rolex tolerances using concreting technology,” he says.

Moore’s quest for precision was rewarded: “Over the full 100m height of the building, the core deviated less than 20mm,” he says.

The real challenge is still to come

TH Real Estate’s office is just a 10-minute walk from the site. In pride of place in its reception is a detailed architectural model of the scheme Moore is constructing. Geoff Harris uses the model to explain how architect Foggo Associates’ distinctive design exploits the constrained site while preserving strategic local views of Tower Bridge. “If you’re clever about your design it gives you the ability to build it quite efficiently, because you’re getting decent floor areas for the amount of walls you build – because the walls are quite expensive,” he says.

The scheme’s 50m by 50m plan means that it takes up an entire City block. Its flanking walls taper outwards to add width to the public footpaths. However, even in its tapering form the office floors are super-efficient, having been designed to allow tenants to subdivide them without wasting space. “As a developer, this scheme is about as textbook as a centre-core building gets: the old magical 12m wall-to-core dimension works perfectly for a range of occupiers,” Harris explains.

There is also a commercial element to Harris’ description of the floor areas because the net floor areas are enshrined in the building contract. “Nick [Moore] must be within 1.5% target area on each individual floor and by total floor area,” says Harris. “If there is a diminution of more than 1.5% from that area then there is a financial penalty because floor areas are what we generate our income from; get it wrong and the consequences are massive,” he explains.

The contract is a two-stage modified JCT with an element of contractor’s design. “It was locked down with Mace at 80% fixity on cost at the second stage with the supply chain procured as part of the process,” says Harris. The project reached 100% surety on cost at Christmas 2017. “It is a testament to everybody working on the project that it sits on budget and it has advanced on programme,” says Harris.

With its current rate of progress, the project’s target completion date of December 2018 is looking achievable. However, Harris knows that the most challenging aspect of the build has yet to come: the works to the rooftop plant room.

The two-storey plant room is located beneath the arched structure at the top of the building, 100m or so above the City’s bustling streets. It will house cooling towers, air handling units and two generators. The space is open to the elements: structural steels arch over the space but instead of glazing, the fins support perforated mesh to help with cooling, coloured to look like glass.

“The building needs to read as one, so instead of glass the infill is a perforated mesh of a colour preselected so that when you look at the building from a distance, the mesh will appear to reflect the light in the same way as the glass does,” says Harris.

Its porous mesh cladding means that the plant room and its plant will be visible. So as not to detract from the form of the building, Harris says that the plant room has to be “beautifully planned” with all plant finished in the same colour. The plant will even be a feature at night. “The danger is that the building’s form might make it look like a boiled egg with the lid off at night, so the plant room will be illuminated,” Harris explains.

“The roof works will be our biggest challenge,” acknowledges Mace’s Moore. In recognition of this, Mace has produced a video animation to show how it plans to sequence these high-level works. “What we must do is get the concrete floors on levels 21 and 22 cast as quickly as we can, because we need the concrete to have cured so that we can waterproof it before we start to land plant on it,” explains Moore. “To save time, we’ll use precast up-stands, pre-coated with waterproofing, around all openings.”

Similarly, much of the plant installation will also be prefabricated. “There is a lot of plant to go in so we’ll prefabricate as much as possible in the largest-sized pieces we can possibly lift using the core-mounted tower crane, which will save us time and help minimise the number of people that will have to work at roof level,” says Moore. In addition, work platforms will be attached to the main items of plant to enable the cladding contractor to safely install the mesh panels from inside the building.

The size of the prefabricated plant means that some elements will be too large to fit through the 12m spacing between structural steels. As a consequence, parts of the roof structure will have to be fitted after the plant has been installed. “The structure has to be installed once the plant is in place,” he says. He admits that the procedure could be “quite risky”, but says Mace has come up with a solution to protect the plant that will ensure the installation is “absolutely precise” – which should ensure that it, along with the rest of the building, meets with Geoff Harris’ exacting requirements.

Project Team

Architect, structural and M&E engineer: Foggo Associates

Cost consultant: Arcadis

Project manager: Second London Wall

Contractor: Mace

No comments yet