Building spoke to Philip Ross from design company Safehinge Primera about the often unseen impacts caused by difficult environments – and how safe doors can actually save lives

The impact that good design can have on our health and wellbeing cannot be overstated. The choice of materials used can dramatically affect our physical and mental wellbeing, improve feelings of support, the level of perceived safety and, perhaps most importantly, how valued people feel as individuals.

For Philip Ross and Martin Izod, placing the needs of people at the forefront of design formed the foundation of their company, Safehinge Primera (SHP). As Glasgow School of Art graduates, good design is in their DNA but, having met Ross on a sunny afternoon in London, it became apparent that compassion is vital too.

What started as an art school project has become a company committed to designing for good. From saving children’s fingers to creating doors that prevent suicide attempts in the healthcare and prison sector, Ross firmly believes in the power of designing the challenges out of challenging environments.

Saving fingers

As students Ross and Izod began working with Nanjappachetty Doraiswamya, a former casualty consultant at the Royal Hospital for Children in Yorkhill, Glasgow. Doraiswamy was increasingly frustrated by the number of children who came into the hospital with a finger hanging off and made a plea to Glasgow Art School for a way to prevent the injuries.

According to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, about 30,000 children crush their fingers in doors in homes, schools, nurseries or shops every year. About 1,500 will go on to require surgery or even amputation.

“A door hinge is centuries old,” explains Ross. ”However, it’s fundamentally a dangerous design. Yet, we blame the kid for getting their fingers in the way.”

In a bid to design out the problem, Ross created a door pivot system which maintains an equal measure of space around the hinge as the door opens and closes, eliminating the potential for trapped fingers.

The next step was to make the design commercially viable, which was helped by Manchester City Council adopting the pivot door system as its standard solution for all primary/SEN schools. The council calculated a potential £500 to £1,000 saving per door compared with introducing plastic retrofit guards that need regular maintenance and replacement – making an important business case for the product.

A friend in need

In 2010, the need for a new door design arose again when a former classmate of Ross and Izod was detained under the Mental Health Act. While visiting him in a mental health facility, the pair were astounded by how the space failed to meet his needs. “The design of this space – a brand new hospital – was holding him back,” explains Ross.

One of our most basic physiological needs is sleep. Before being admitted, Ross’s friend had not slept for days. He was in a crisis and required a space to support his additional needs. Instead, the door leaked light through gaps around the edges and glass observation panels created shadows of people walking past all night.

For Ross the connection between the patient’s health and their environment was clear: “We often think of peoples’ behaviour in these challenging environments as something in isolation. I believe it’s more often than not a reaction to something else – and the limited evidence supports this too.”

Few studies have examined the possible influence of architectural features on outcomes in these facilities. However, what research there is demonstrates that a poorly designed, noisy facility that prevents privacy can intensify the stress of mental illness.

Control over the environment – temperature control, clear sight lines and a connection to nature – was all cited as an important factor in reducing aggression and anxiety in mental healthcare facilities, aiding patient recovery and improving staff wellbeing. “Increased self-worth reduces suicidal ideation,” says Ross. “The trick for architects and designers is to understand how you can create positive reactions.”

This led Ross and Izod back to what they do best – fixing a badly designed door.

More than just a door

The doors in and around mental health hospitals are prime examples of the dual function of barriers. A door is not only a physical barrier but can also act as a symbolic barrier, a reminder to patients about their lack of freedom.

It also poses a safety risk, with 51% of suicides in mental health facilities involving the use of a door.

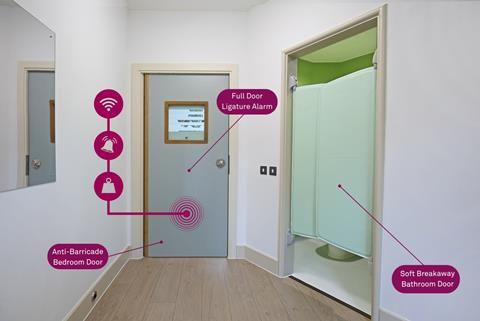

SHP’s design solution hopes to give patients a sense of ownership while retaining overall control to ward staff. Service users can lock their bedrooms, which combats the frustration of not having a key and the unhealthy power dynamic this creates between the user and staff.

Anti-barricade technology also provides staff with an override option to use in emergencies, pulling the door outward in case of a lock-in, while a soft breakaway bathroom door increases monitoring capabilities conducive to privacy needs.

The full-door ligature alarm has a weight sensor which sets off a discrete alarm during a suicide attempt and a digital platform allows staff to reduce their response times and make improvements internally.

A mental health ward in the south-east of England installed the full-door ligature alarm system in their facility and found the technology invaluable. Accurate data enabled the team to revise internal processes, consistently lowering their response time from 1 minute 17 seconds to just 24 seconds, and reducing the number of successful ligature attempts to zero.

By 2018, SHP had supplied its doorsets to over 80% of NHS trusts.

Prisoners are people too

In 2014, the team were approached by the project lead from the Scottish Prison Service, who was seeking a door design for its new facility in Stirling. Responding to a report by Elish Angiolini which highlighted that 80% of women offenders had poor mental health, the prison service was forced to design a hybrid custodial/mental health facility.

Ross and his team joined a nine-year development process to co-create a door that resolved the institutional noises of hollow steel while keeping offenders and staff safe. Custodial doors need to work differently as, in a secure custodial setting, the door is a natural attack point, presenting potential weaponisation temptations.

The finished product was a timber-based custodial door with a softened visual panel and anti-ligature hardware, as well as custodial security, such as fire performance and class 1 custodial locks. According to the team, the door survived a significant robustness evaluation by the prison service, to avoid any safety concerns that a failure could prompt.

The new facility, HMP & YOI Stirling, was completed in 2023, replacing HMP Cornton Vale. Designed by Holmes Miller, it hopes to be an example of a therapeutic approach to prisoner wellbeing.

Despite noise complaints from the nearby housing estate that the prison is trying to manage, the hope is that this wellbeing-focused approach to prisoner care will aid their rehabilitation.

Ross says: “Our business is focused on helping to protect people at a vulnerable time. This can apply in many different spaces.

“In its simplest form, this is protecting a child’s fingers as they play with friends at nursery, or it can be protecting distressed and suicidal service users in a mental health hospital, and more recently protecting offenders during their time in the care of a prison.”

Project X

Protecting people at a vulnerable time has been the driving force for the company’s latest product launch, Project X. The launch arrived as a counterbalance to Oxevision, a surveillance camera on the market and finding its way into mental healthcare facilities across the country.

Described as the first digital observation tool for mental health, the monitoring system prompted concerns within the industry due to the risks associated with surveillance.

Mental health physicians are seemingly stuck between a rock and a hard place. With 91% of suicides in mental health facilities taking place in private spaces (63% in bedrooms and 28% in bathrooms), the need for monitoring is just as important as the need for privacy.

Countless anecdotes from patients expressing feelings of discomfort and paranoia with changing in a room that has cameras led SHP to take on the job of designing an alternative. Still in its infancy, Project X is a patient safety aid that uses a radar instead of a camera, allowing for patient observation without compromising privacy.

The non-visual sensors can be located in the highest-risk areas and a digital platform will provide staff with the data they need including location, heart rate and level of perceived risk (without a visual image of the service user).

Ross hopes that the sensor will provide a way for staff to have full insight, increasing safety, while also giving service users the privacy and dignity they deserve.

Good design can take some of the challenges out of the most challenging environments, moving people from merely surviving to thriving.

“When someone is in a vulnerable place – detained under the Mental Health Act, serving a sentence in prison, or wherever they might be – the built environment can expose you to the greatest dangers,” says Ross. “Or it has the opportunity to be a place of physical and/or psychological safety.”

No comments yet