As part of the Building Your Future campaign, we ask what buildings were futuristic in their time, or marked a change in how the industry built. Here, architect James Bell of MSMR Architects acclaims the innovative design and economic robustness of St Pancras station and hotel

The pace of change in the 19th century would make modern London look stationary: all 10 of London’s rail terminuses were built within a 60-year period.

When the Midland Railway Company won the right to operate a new route into the capitol the search began for a site for its terminus. Land to the west of the new Kings Cross station was identified, served by the Regent Canal and easily connected to their existing lines. Unfortunately, it was occupied by Old St Pancras churchyard. Despite being the oldest site of Christian worship in England, Victorian pragmatism prevailed and 88,000 bodies were dug up for reinternment (overseen by a young Thomas Hardy, yet to eschew architectural life for that of the novelist).

The station was to make a grand statement about the company’s civic aspirations. Whilst private ventures on this scale are rare today, one part of the design story remains familiar: the famous architect and the less well-known engineer. Both created unique, innovative designs destined to suffer, but survive, economic forces. On one hand was William Barlow, chief engineer, responsible for the platforms and their enclosure. On the other, designing the associated hotel, was Sir George Gilbert Scott, celebrated architect, at the height of his fame having won the Albert Memorial commission. Nairn’s London sums this up in characteristic pithy style: “Shed, W.H. Barlow, 1858; Fancy work, Sir George Gilbert Scott, 1874”

The scheme’s mixed-use nature, whilst familiar now, was less common at the time. As well as introducing new alternate income streams it attempted to bring life to a building type which often interacted poorly with its surroundings.

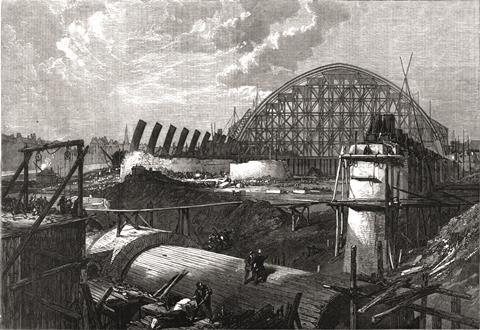

The trainshed was a masterstroke of functional design and engineering daring. The roof is made up of wrought iron ribs creating a space 30m high, 73m wide and 213m long. It was the largest single-span roof in the world when built, and was copied across the world, including Grand Central Station in New York. The elevated platforms allowed trains to cross the neighbouring canal and provided storage for freight (principally beer) in the under croft.

The hotel, seen as the apogee of the Gothic Revival, was described as the most sumptuous in London. It went greatly over budget though - empty plinths can still be seen today where statues were originally planned. Inside it had some innovative features: hydraulic lifts and revolving doors, but it failed see the coming ubiquity of domestic plumbing and its lack of en-suite facilities hastened its decline, resulting in closure in 1935.

From 1930s onwards, the hotel was used as offices. After the war the trainshed under croft became redundant as freight shifted from rail to road. In 1968 a proposal was made to demolish and redevelop both St Pancras and Kings Cross. It was ultimately unsuccessful (thanks to Betjeman among others) and resulted in the station being awarded grade 1 listing. From that time the hotel building was mothballed and slid towards dereliction.

A ray of light emerged in 1993 when the Government decided upon a high-speed route for Channel Tunnel trains to London terminating at St Pancras. A new underground link to Kings Cross, following the tragic fire of 1987, and its inclusion on the Thameslink line added to the extensive redevelopment, which was completed in 2007. The undercroft was reborn as the ticket hall and retail concourse, with platforms above extended to accommodate the longer Eurostar trains. The hotel building was comprehensively refurbished to house, once again a hotel, with private apartments above.

Both structures are testament to their robustness and flexibility, and to our ability to creatively re-use our heritage. They are once again world-renowned and are a hub for many varied uses. Where once a station could blight its surroundings its potential to stimulate vibrancy and growth is now understood.

Postscript

James Bell is a director of MSMR Architects

No comments yet