Will the UK’s biggest projects ever be built on time and to budget? Despite recent evidence, it’s not impossible to think that they might – but some things have to change, Dave Rogers reports

Recent news that the northern leg of the HS2 railway line could now be on the chopping block has prompted more eyerolling from the industry.

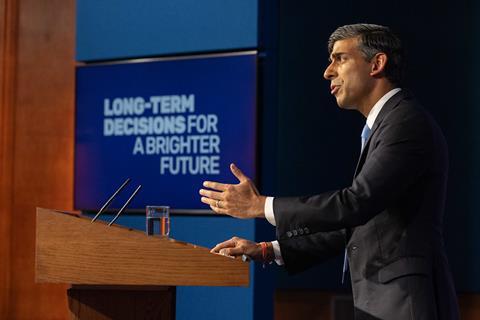

An eagle-eyed press photographer outside the Treasury snapped a picture of documents relating to a meeting between prime minister Rishi Sunak and his chancellor Jeremy Hunt. They included costings for the later phase of HS2 – which would take the high-speed rail scheme from Birmingham through to Manchester – and outlined the potential savings that could be gained from cuts.

The government has already spent £2.3bn on this second phase of HS2, which could not be recovered even if the job were to be shelved. But ministers believe cancellation could save the Treasury £34bn in planned expenditure.

>> Find out more about the Building the Future Commission

A government spokesperson subsequently gave a vague commitment to delivering “the project”, without explicit reference to the later phase. But Building understands the news about Manchester – the bit which the documents said might be axed – came as a surprise to officials at HS2 who had not formally heard about it. The lensman, it seems, told them what the government had not.

Henri Murison, chief executive of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership, spoke for many when he said: “This isn’t just about changing the way that people might be able to get to London or to Birmingham. This fundamentally rips up the entire basis of the commitments that Rishi Sunak as chancellor made to the north of England.”

He added: “What do we say to all those inward investors who have come to Manchester?”

On hearing the news, Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham put it more bluntly: “Levelling up? My arse.”

This fundamentally rips up the entire basis of the commitments that Rishi Sunak as chancellor made to the north of England

Henri Murison, Northern Powerhouse Partnership

Sunak and Hunt are also reportedly mulling even more cuts on the railway, potentially making the decision to mothball a terminus at Euston a permanent one. What to do, then, with a huge hole in the ground described to Building this year as “a scar on London” by Mace chief executive Mark Reynolds? No one seems to have any idea.

Last week Sunak announced yet another U-turn. This time a host of net zero targets – set out by the Conservative government he was part of, remember – were delayed.

>> Also read: ‘The design team has gone from 500 to six.’ What HS2 Euston is doing now

>> Also read: There is nothing long-term about Rishi Sunak’s net zero policy U-turn

Sunak was part of the same government that waved through the decision to press on with HS2. “He was chancellor when these decisions were being taken,” said one industry insider. “It’s not like he was stuck at the other end of the table.”

Tellingly, there does not appear to be any record of Sunak having gone to visit this country’s flagship infrastructure project. Boris Johnson did so when he was prime minister and Hunt paid a visit to HS2 near Birmingham soon after becoming chancellor last autumn. But, for Sunak, the scheme has so far been a no-show.

The recent flip-flopping by the prime minister matters for all sorts of reasons, but such an inconsistency in policy-making certainly sends a message to business that the UK cannot be relied upon: this is a country that keeps changing its mind. It gives the impression that our government is incapable of honouring a commitment.

This was a point made at the weekend by National Infrastructure Commission chair Sir John Armitt. “If we don’t continue, what are we saying to the rest of the world?” he told the BBC. “What are we saying to all those investors who we want to bring into the UK. Here is a country that sets itself ambitions and then runs away when it starts to see some challenges. We have to meet the challenges.”

If we don’t continue, what are we saying to the rest of the world? What are we saying to all those investors who we want to bring into the UK

Sir John Armitt, NIC chair

This adds to the poor optics that big infrastructure jobs have. They always cost more than the original budget, the narrative goes, and so they always have to be pared back. Maybe the budgets were never realistic in the first place?

Hunt says costs are getting “totally out of control” as if HS2 is spending money without a care in the world. It seems only a party which blew an estimated £60bn on a ditched mini-Budget has the wherewithal to ride to the rescue and bring spending under control. In any case, most working on the job know that the numbers are under constant scrutiny. “HS2 are always looking to optimise the programme,” said Kier chief executive Andrew Davies at the firm’s recent annual results.

HS2 is having to live in the shadow of previous failures to stick to outlined budgets and finishing posts. Crossrail is the most recent example of that.

Due to open in 2019 it finally opened last May and was billions of pounds overbudget – although few who regularly use it now remember those woes and instead marvel at the time to be saved when getting from one side of London to the other.

Transport for London says the Elizabeth line, the new name for Crossrail, is now beating post-pandemic passenger number forecasts. In its first full year of operation, it carried just over 150 million passenger journeys. Definitely not the white elephant some had feared it could be with the pandemic leaving some to wonder how well-used the line would be in the wake of changing working habits.

Sir John Armitt will be speaking at this week’s Building the Future Conference

NIC chair Sir John Armitt is the keynote speaker at the Building the Future Commission Conference in Westminster on Wednesday. You can join us to hear from him and other leading figures from across the construction industry – and find out more about the work of the commission.

The day will include panel debates on net zero, digital transformation and building safety as well as talks from high-profile speakers on future trends and ideas that could transform the sector.

Other keynote speakers include Katy Dowding, president & CEO, Skanska UK, and Martha Tsigkari, head of the applied R+D group, Foster + Partners.

There will also be the chance to feed in your ideas to the commission and to network with other industry professionals keen to share knowledge.

You can follow our progress using #BuildingTheFuture on social media.

So, how to make big infrastructure schemes less susceptible to cost blowouts and massive delays? It is a question that has dogged the industry for years.

The Building the Future Commission makes no promises with the offer of a silver bullet. Some things seem obvious, however.

One area to improve is UK construction productivity, while inefficient payment plans and onerous project management practices mean that current industry margins average around 2%.

As a consequence, constructors’ ability to sustain investment in the technology required to drive change is stifled, projects typically run late and over budget, companies fail and jobs and livelihoods are lost.

Best known for building stadiums, this is a blueprint of what happened, in part, to Buckingham which collapsed into administration earlier this month after nearly four decades in business. The firm had been targeting a £700m turnover this year. Instead, nearly 500 staff are looking for new jobs.

It is telling that the only bit of the Buckingham business that interested would-be suitors was the rail business, in other words the infrastructure bit.

Explaining the move to buy it, Kier’s Davies said: “We have previously stated that we would consider value accretive acquisitions in core markets where there is potential to accelerate the medium-term value creation plan. This acquisition is one such example.”

Davies and others turned down the chance to buy the remaining bits of the business, noticeably Buckingham’s building arm. Too much risk, presumably.

Laing O’Rourke – with its championing of MMC and off-site, its pool of labour and in-house businesses such as M&E contractor Crown House and concrete frame arm Expanded – has more than most been trying to drive change in the wider industry.

It argues that more collaboration on infrastructure schemes between private sector and public client is needed.

A spokesperson says: “A ‘delivery partner’ approach is emerging in some government departments, particularly through the MoJ and MoD. The sector needs end-to-end partnership with public sector clients so that procurement is quicker, programme and costs are clearer from the outset and delivery risks are shared equitably.

“Punitive penalties should be replaced with incentivisation based on achieving outcomes. Positive organisation design – making it a collective responsibility – would help to set the right deadline and incentive for each outcome.”

As well as changes to procurement strategies, certainty of work – not more chopping and changing of the kind that HS2 has endured – is another point high up firms’ wish-list of how to do things better.

James Corrigan, UK managing director of infrastructure at consultant Turner & Townsend, says: “There is growing consensus that what we categorically need to see is long term-commitment, so that the industry can have the confidence and resources it requires to deliver to its full potential.”

But he admits: “The sector is in a more difficult phase. Insolvencies have increased as government pandemic support has been pulled back and, in a tight fiscal environment, spending on some of the most significant infrastructure pipelines has been delayed or paused.

“There are direct consequences as a result into R&D and other initiatives in place to drive greater productivity and performance from the sector. We continue to struggle with skills shortages.”

Corrigan also says that the politics needs taking out of infrastructure. “For this to succeed, it requires a shift in mentality from government and a commitment to take a longer-term view which looks beyond election cycles and the next fiscal announcement, even if current policy was introduced by different ministers or a different party.”

But, he admits, this will be easier said than done: “This may not come naturally to government, but getting it right would put infrastructure in a much better place to flourish and fulfil its potential for the benefit of the country as a whole.”

The creation in 2015 by then chancellor George Osborne of the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) was designed in part to address uncertainty and bridge political cycles.

But how difficult this has been was underlined when Armitt, frustrated by the uncertainty dogging HS2 this year, told Building in March that the government should stop dithering and “just get on and build the thing”.

His point was that the decision to build it had been made – and needed following through. Delaying bits of it would not save money in the long run.

He elaborated on this at the weekend, saying: “There are massive benefits to the economy by continuing this.… the benefits from Birmingham to Manchester are £55bn… and you are increasing the benefits across the whole of the north west because in fact it will connect in to the improvements that government has announced between Manchester and Leeds, so you have a whole connected railway.

“You control the costs, you don’t run at the first whiff of gunfire. You buckle down and you address those cost issues and you address them on a daily basis across the whole project.”

“With these big projects, once you’ve made a decision, you have to stick with it,” says Arcadis chief executive Alan Brookes. “We do seem to have this stop-start attitude in this country.”

Bill Hocking, chief executive of Galliford Try whose £600m infrastructure business concentrates on highways and water work, admits: “It’s a balance between needs and democracy. The interest [in building infrastructure] is there, but getting things actually moving takes forever. The process to get in the ground and get going can take a long time and costs a fortune.”

Keltbray has been growing its infrastructure business in recent years, working on rail schemes as well as highways jobs, and more so since it picked up parts of collapsed contractor NMCN nearly two years ago.

It says, going forward, that clients and contractors need to “cultivate trusted relationships which embrace sharing of information, break down ‘old-school’ preconceptions, avoiding entrenched positions and promote collaborative working towards shared goals”.

It adds: “[There should be] recognition that organisations are operating within a cash-limited, resource-poor environment. Pooling skills and resources across functional areas will maximise the effectiveness and impact on effective planning, funding and delivery.”

Initiatives to improve delivery are out there, like Project 13, an industry-led response to infrastructure delivery models. It was set up in 2016 by the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Civil Engineering Contractors Association and the World Economic Forum.

Its core message is that the transactional model for delivering major infrastructure projects and programmes is broken. They say that it prevents efficient delivery, prohibits innovation and therefore fails to provide the high-performing infrastructure networks that businesses and the public require.

It said shifting to an enterprise model for infrastructure delivery is core to the Project 13 approach. In short, this brings together owners, partners, advisers and suppliers, working in more integrated and collaborative arrangements, underpinned by long-term relationships. Participating organisations are incentivised to deliver better outcomes.

For now, it seems the next few weeks will be crucial for HS2. It is too late to stop work on the first phase between Old Oak Common and Birmingham Curzon Street – even this government knows it is in too deep to U-turn on this one. But for the rest of it – the stretch to Manchester and the station at Euston – no one is sure. Sunak and Hunt could be making a decision on it as soon as this week with the autumn statement on 22 November seen as the hard stop for when clarity will be provided.

The lobbying to keep HS2 going has begun with news that more than 80 companies and business leaders, including British Land and Manchester Airports Group, writing to government to get clarity over the commitment to HS2, arguing that that repeated mixed signals are damaging the UK’s reputation. They expressed “deep concern” over “the constant uncertainty” that “plagues” the project.

Former prime minister Boris Johnson, who gave the green light to start construction more than three years ago, said “desperate truncations” would not yield any short-term savings and added: “It makes no sense at all to deliver a mutilated HS2.”

Everyone can agree that improving delivery of big infrastructure schemes is desperately required. What is needed is cross-industry and cross-government departmental coordination to identify the best examples.

This requires long-term thinking and planning. However the travails of HS2 and now the net zero initiative show that this is in rather short supply.

12 ways to make infrastructure projects run on time – and to budget

Try taking the politics out of infrastructure

Admittedly, this is difficult given that most schemes are funded by the taxpayer. But the goings-on at HS2 are surely the clearest case for this argument.

Take one example: at the start of the year, the government said it was committed to ending the line at Euston. Then it mothballed the idea a few weeks later and now it seems to be preparing to ditch the plan entirely. In the mean time, a vast swathe of land in central London remains unbuilt on and earning no one anything – apart from fees for the security firms asked to look after it.

Become more collegiate

A delivery partner approach removes some of the competitor tensions, drives collaboration, improves value for money and accelerates delivery.

Improve margins

A familiar refrain, but why not agree a margin at the start of the contract and stick to it? Mid and post-contract arguments would be removed at a stoke.

Set realistic budgets, rather than the current hit-and-hope method

Can infrastructure jobs ever be on budget given they are years in the making and things like technology advances on schemes tend to jack up prices? It is a moot point. Geopolitical issues such as the war in Ukraine and rampant inflation of the kind seen last year can also throw budgets into the bin. Still, punitive penalties can be ditched and swapped for an incentivisation model, based on achieving outcomes.

Improve productivity

The sector’s record has long been a source of angst and it shows no real signs of improving by the leaps and bounds required. Manufacturing and assembling offsite helps this and will also banish well-worn impressions about this industry: that is stuck in the past and slow to change.

Doing this might also create new technology-led roles which excite more people about the prospect of a career in construction.

Stop comparing the UK with places like China and get the messaging on costs better

HS2 is using around 65 miles of tunnel on the 140-mile route between London and Birmingham because people do not want to see miles of countryside ripped up. That costs more money.

This is what National Infrastructure Commission chairman Sir John Armitt told Building in March: “In countries which are democracies, we can’t just drive a cart and horses through local concerns. There is no infrastructure without politics. There is more representation and articulation of concerns at a local level now but, equally, it potentially makes it more difficult to proceed with some of those projects.”

Make contracts less onerous for firms

Contractors complain that an unacceptably high burden is put on them as the construction partner to bear the operational and financial risk of delivering complex schemes. This needs fixing.

Ensure certainty of work

A firm pipeline allows businesses to plan resources and invest in skills and capacity across the board. It provides the right conditions for money to be spent on digitalisation and productivity improvements. Large upfront costs can be difficult to justify in the absence of visibility of work.

Give greater authority and importance to the NIC and the Infrastructure and Projects Authority

A commitment to continue support for the NIC and its existing priorities in party manifestos would be a mandate to the IPA to continue its work to support the delivery of government-led programmes, whichever party is in charge.

Stop dithering

Remember the Davies Commission? Also known as the Airports Commission, it was set up in 2012 to “consider how the UK could maintain its status as an international hub for aviation and immediate actions to improve the use of existing runway capacity in the next five years”.

It made its recommendation – to build a new runway at Heathrow. That was in July 2015. Since then, nothing has happened. The pace of the central decision-making processes on major infrastructure schemes needs to radically improve.

Less secrecy, more openess

Firms should share data, combine knowledge and skills to get most value for money.

And finally, a message for government: once you’ve made the decision, stick to it.

No comments yet