Last week Berkeley Homes went to war with Michael Gove over the design quality of a scheme in Kent, but locally-adapted design codes mandated in proposed new legislation are meant to help avoid such conflict. Ben Flatman speaks to professionals from across politics and the planning process about the potential of the codes and the impact they are already having

The planning system has become an increasingly fraught topic of conversation for many within the construction industry. Views range from those who think it just needs better resourcing to those who believe it requires root and branch reform.

Few are happy with the way things stand. As Victoria Hills, chief executive of the Royal Town Planning Institute, says: “Public confidence in England’s planning system is at an all-time low.”

Last week Berkeley Homes announced that it was mounting a legal challenge against the government after Michael Gove blocked its planning application for 165 homes in Kent on “design grounds”. Gove’s intervention went against the advice of a planning inspector.

Could new government legislation – and specifically design codes – help to unlock the deadlock?

Proposed changes in the Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill currently going through parliament will require every local planning authority to produce a design code for its areas. These codes will have “full weight in making decisions on development”.

The fact that the secretary of state is intervening at such a micro level, and on the complex and highly subjective question of design quality, is a concern to almost everyone in the design, planning and housebuilding sectors. With such uncertainty comes increased costs and, potentially, a growing reluctance to invest in housing.

Many small and medium-sized housebuilders have already left the market because of the perceived risks. Now the major players, such as former Redrow chief Steve Morgan, are accusing the government of setting out to “destroy” the industry.

Gove’s move appears to be part of a wider attempt by his department to drive up design quality in housing. But it is antagonising many within the industry and risks tearing the government apart.

An influential grouping of Conservatives on the centre right believes the problem can be solved by improving design and delivering housing and development that enhances a sense of place. Once people start seeing that new developments can improve the quality of their local environment, they will stop resisting new housing – or at least, that is the theory.

The hope is that introducing design codes will help drive up standards

The Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission was an attempt to reframe the planning system around more defined concepts of quality, or “beauty”, and a clear commitment to creating enduring and successful new places for people to live and work. A core theme was requiring new development to make reference to context and the specific qualities of individual locations.

The commission’s work has informed the government’s Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill, which includes some of its key recommendations, notably the use of design codes.

In July 2021 the government published its initial National Model Design Code which, it says, “sets out clear design parameters to help local authorities and communities decide what good quality design looks like in their area”. Two phases of government-funded pilots have taken place, to assess the challenges that planning authorities will face when rolling them out.

The code “forms part of the government’s planning practice guidance and expands on the 10 characteristics of good design set out in the national design guide, which reflects the government’s priorities and provides a common overarching framework for design”.

The hope is that design codes will not only help to drive up standards but give power to local communities and introduce more certainty for investors. But will the proposed changes address the concerns of the construction industry and meet the needs of wider society?

As part of the creating communities stream of the Building the Future Commission, Building’s ambitious 12-month project to improve the built environment, we asked what a range of industry figures think of Gove’s design code revolution and the extent to which the idea could help drive positive change.

Here are the views of some key players from across politics, design and planning. We asked them what design codes mean and what challenges they present for the planning system, local government and designers.

The urban designer

David Rudlin is a director at BDP and worked on the development of the National Model Design Code.

He believes the challenges the UK faces around quality and placemaking are “a legacy of design problems going back decades”. As a result, he cautions against seeing design codes as a quick fix.

But he does believe that they should help local authorities get the fundamentals of good design right. “Design codes are more about the basics, which are the things that normally go wrong,” he says.

By providing clear guidance, codes will theoretically make it easier and quicker for planning officers to make decisions. This even includes officers “who aren’t design trained,” says Rudlin.

“The whole point of coding is that you don’t need to be a skilled designer to implement it. They are therefore a good alternative to having to train up hundreds of planning officers.”

But Rudlin is deeply aware that design coding is largely alien to the UK planning system. “Codes are designed for non-discretionary planning systems,” he says. “Putting a non-discretionary tool into a discretionary system is where the issues will arise.

“In France, if you follow the rules, you can get building consent over a counter. Will it be that simple in the UK?”

For codes to be a success, he believes that it will be critical for planning officers to have political backing so they can take decisions and know that they will be supported. “A development manager needs the confidence to refuse something that doesn’t meet the code – and know that they will be supported on appeal.”

Rudlin stresses that design codes “don’t need to be complicated” and believes councils should be wary of appointing external consultants, who he believes tend to overcomplicate the process. “They can be just 30 to 40 pages long. They’ve got to be as simple as possible if they are going to be useful”.

The planner

Vicky Payne is strategy, research and engagement lead at the Quality of Life Foundation. She also worked on the National Model Design Code with David Rudlin.

She sees design codes as a potentially useful new tool, but not a simple panacea for all the planning system’s ills. “I think they’re something that have a huge amount of potential within the right conditions,” she says.

To work well, she believes that design codes should be implemented within a context where there is strategic spatial planning and an updated local plan. “With those elements in place, then design codes would be a functioning part of the policy system,” she says.

“In theory they make decision making quicker at the later stages of the planning process.” But Payne questions whether they will actually reduce the pressure on planning departments. “They don’t reduce the workload overall. They just frontload the work.”

She points out that capacity in planning departments is “a massive issue” but believes that, with the right resources, the existing planning system could deliver.

“A lot of the time the planning system is pointed to as the source of all ills,” she says. “I would love to see how the current system functions when resourced properly.

“Let’s make that a priority while we explore how the system itself could be improved.”

The architect

Simon Bayliss is a partner at HTA. “Design codes unquestionably have a place” he says, before adding that the most successful codes “tend to be quite flexible on style and materials”, with a consistency on heights and density.

But he underlines how time-intensive producing design codes can be. They require “quite a big team”, he says.

And he references the “huge lack of resources available to local authorities” and a lack of decision-making authority in local government. “Most Local authorities lack the time and specialist resources required to prepare design codes themselves.”

He believes design codes can work “if you are able to develop a really clear vision of the quality of the place you are trying to create and for which local support can be gained”. But Bayliss argues that a multidisciplinary approach is crucial, with attention to landscaping and streets. “My fear is that it’s not an easy thing to do.”

Bayliss provides Dunton Hills Garden Village as an example where a site gained allocation and support for development through investment in a design code. He also points to Poundbury – “controversially, perhaps” – as an example of where he believes design coding has been done well. “Regardless of ones view of the architectural style, it’s clear that the design code has achieved what it set out to do.”

When asked what local authorities need, he emphasises “a properly resourced planning team”.

He adds: “Austerity since 2010 has hit planning departments hard. A cynical view might be that design codes are being promoted by government as a replacement for the erosion of available skills in local planning teams.”

The regeneration specialist

Tom Bridgman is executive director for development at Oxford City Council and has worked in the private sector as an associate director for Aecom, before moving to public sector regeneration at Lambeth borough council and then in Oxford.

He sees the potential value in design codes but worries about how local authorities will resource their production and wonders “whether it will be one code or a series of codes” that councils are required to produce. “We will be watching closely,” he adds.

“Design codes are a really effective tool at the site level,” he observes. But he sees the amount of work required to create the codes as being in conflict with their stated role of reducing planners’ workload. “There’s a question about the level of resources needed to develop a set of design codes across the whole city.

“When it comes to placemaking, local government could be so much more central. We have some amazing tools. If the levers are pulled at the right time, we can produce some incredible outcomes. But it often feels like we’re in a boxing match with one hand tied behind our backs.”

A key challenge that Bridgman identifies is in finding and retaining sufficient staff. “We have some fantastic talented members of staff, but need more.” Discussing the diffifculty in appointing some of the more senior planning positions, he says: “It’s a continuous struggle in terms of competing with the private sector on pay.”

The social enterprise leader

Pooja Agrawal is CEO of Public Practice, a social enterprise that works to address skills gaps in the public sector by recruiting from the private sector.

While acknowledging that planning departments have faced significant cutbacks, Agrawal sees the move to introduce design codes as good news. “It’s positive that the government has recognised the role of design and that design is being linked to quality of place.”

She believes that pushing design codes will enable local authorities to take a more “forward-looking approach” to creating place.

“It’s basically about identifying what is unique and special about your place and building on that,” she says. “It could be built heritage, but also culture more broadly. As a concept it’s really good.”

Agrawal also identifies resources as a key challenge. “How much are local authorities going to be able to do this in-house rather than through outsourcing to consultants?” she asks.

Public Practice’s most recent recruitment and skills survey showed that a third of local planning departments were not sure they could fulfil their statutory duties. Agrawal points to the Institute of Government’s statistics that show a 37% cut in central government funding to local authorities between 2009/10 and 2019/20 – a fall from £41bn to £26bn.

Spending on planning departments has fallen by around 43% over a similar period. “Obviously it has a huge impact on what local government can do,” she says.

She worries that local government currently lacks the capacity and skills to do the more “holistic thinking” that is required before design codes can be properly produced and implemented.

Although local authorities see funding as a major problem, she says that 79% also said that their biggest issue was attracting “the right people with the right skills” to address “architecture, urban design and sustainability”.

With some of Public Practice’s associates having worked on the design code pilots, Agrawal says the feedback has underlined the need for the right skills to be in place. “You need the right skill-set to set out the vision – to facilitate, even if you don’t have all the skills in-house. Even to commission you need the right skills to ask the right questions.

“Local authorities want to be able to do this but don’t have the people to do it. It’s about different types of skills needed to address these issues.”

The local councillor

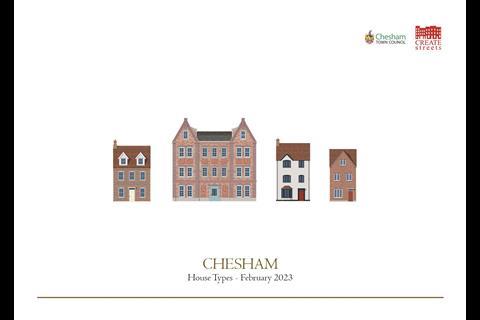

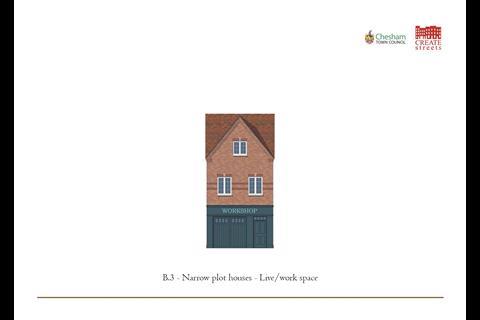

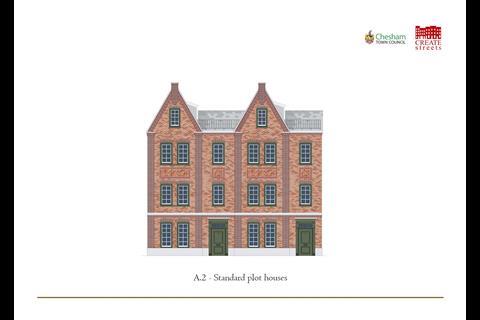

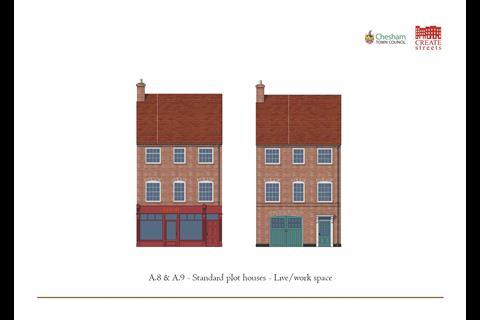

Nick Southworth is a Conservative councillor on Buckinghamshire County Council and Chesham Town Council. He chairs the neighbourhood plan committee for Chesham and has been working on a design code for Chesham and the local plan for Buckinghamshire, which is at the call for sites stage.

“Nimbyism has understandably grown because people have seen so much poor development going into their towns,” says Southworth, who sees design codes as representing the “democratisation” of local planning.

He describes how “the 1960s and 70s rolled in and bulldozed a lot of the town”. He wants to “enhance the town for many years to come”.

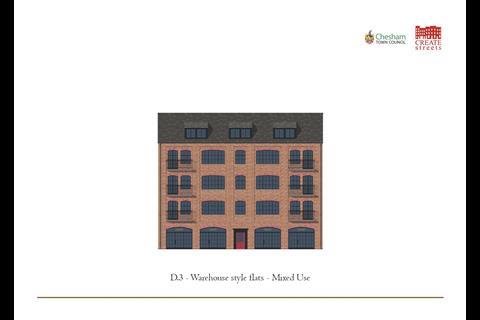

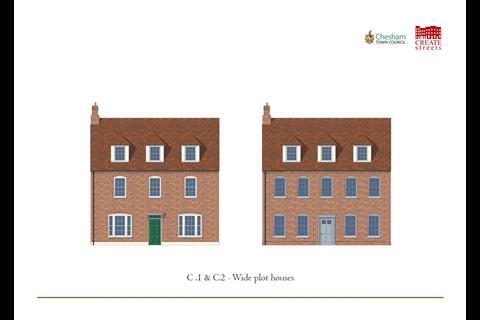

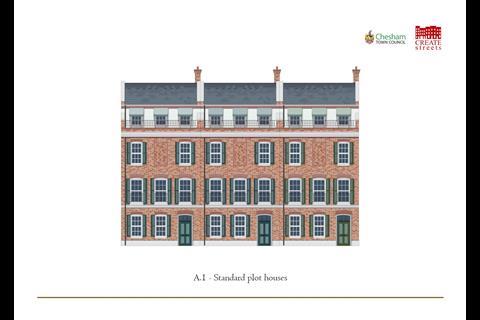

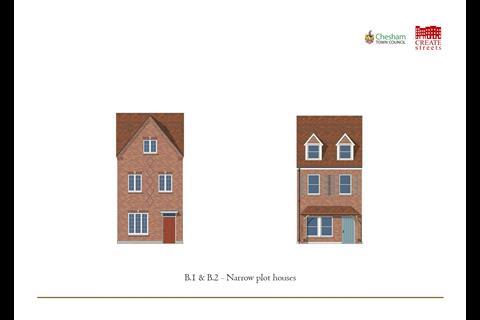

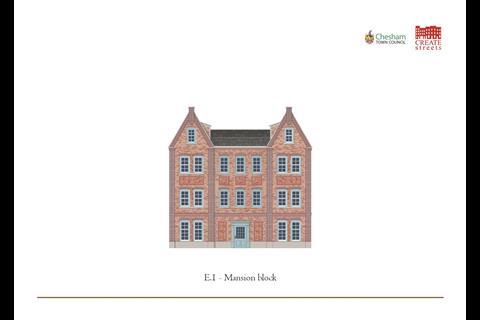

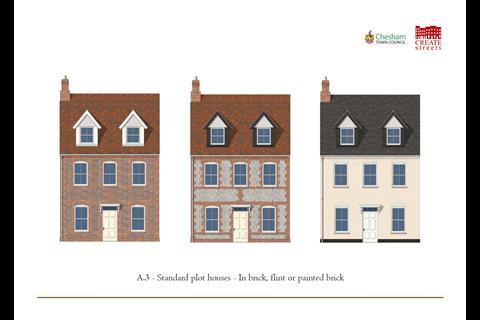

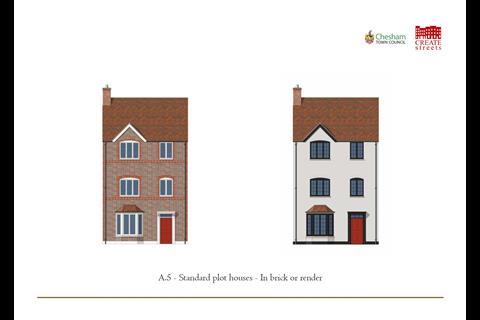

Chesham Town Council is using design codes to steer development on an old brownfield site. “Design coding is fundamental to the whole project,” he says. “The end product will be something local people can recognise that they have had input into.”

Southworth has been working on the neighbourhood plan since before covid. When the Levelling Up Fund was announced, Chesham put in an application for funding. Since then he has been working hard to develop a design code for the site. “It’s about reflecting what the town wants to see,” he says.

He knows developers have the money and are keen to build, but struggle to navigate the planning system. “We’re de-risking the planning for the developer, but the benefit is [that] we get the development we want – and homes.”

Southwork sees design codes as sitting “between directive planning and laissez-faire”, and believes communities need to embrace the opportunity “if we don’t want the directive approach thrust upon us”.

The neighbourhood development orders will come to a public referendum and the democratic process means the town has the opportunity to throw out all of Southwork’s work. He admits he would be disappointed if the local community voted against the plan, which includes the design code but accepts that the town must have the final say.

In the end the design code has provided around 13 different housing typologies “native to Chesham”. It includes a very detailed palette of materials – including hung tiles and brick.

He admits that for all councillors there’s a “political risk that we upset residents. Development is always emotive, which is why so many councillors are wary of engaging in it”. But the payoff is worth the risk. “What we desperately need is homes for people. If we want the houses to be on brownfield, not green, we need to put this work in.”

He describes the approach to producing the design code as complex. “We started the design coding as a blank canvas and then sought residents views on what they liked and received thousands of responses.” The approach involved allowing local people to nominate any of the buildings in the village they liked.

“People chose buildings predominantly from 1850 to 1930,” he says. “They gravitate towards those traditional styles.”

He describes the approach of most architects, who he sees as dogmatically advocating for modern design, as being akin to “cooking dinner for a vegetarian and serving them steak”. He adds: “Keep building homes people don’t like and you will carry on getting opposition. We have done the market research for developers, you know what the market here wants to buy, why wouldn’t you then want to build it!”

When asked whether this means that contemporary design will still be an option for those who want it, he says he is “not here to enable what people don’t like”. The “town had enough of experimental architecture,” he says.

For Southworth, it is all about meeting the demands of his constituents. And he sees significant broader benefits. “If you build in styles people like, you’ll get away with greater densities. Give the people what they want.”

The Office for Place’s 10 guidelines for successful design coding

1. Set a clear vision of ambitions for the site.

2. Align with local and national policies and be evidence based.

3. Find out what people really like and want.

4. Keep codes clear and short, visual and numerical wherever possible.

5. Keep them practical and achievable.

6. Set definitive requirements using words like “must”, “will” and “required”. Guidance can be added using words like “could” and “should”.

7. Keep them real.

8. Keep them relevant to the area with appropriate density and context.

9. Make sure they are enforced through a process of approval.

10. Allow them to change over time if circumstances dictate.

The commissioner’s view

“Over the past 70 years, this country has conducted an experiment. It has chosen to run its planning system in a method almost unique amongst both Code Napoleon and common-law countries. It has placed a far greater focus on case-by-case development control decisions and far less focus on clear guidelines which everyone can understand and follow.

Our approach is not without advantages: it can cope well with the complex and the weird. But it also has serious challenges.

To run well, it is a Rolls-Royce system, which requires challengingly high levels of local staffing and expertise. It is best suited to rich areas and those with deep pockets and good lawyers, able to navigate the uncertainties of the system.

It excludes the self-builder, the entrepreneur and the local builder. It punishes “left behind” places. It over-engineers the difficulties and increases the planning risk and un-fundable pre-planning cost of just creating good ordinary homes and places.

It is no coincidence that we have one of the most concentrated development markets in the world and some of the steepest supply and affordability challenges.

Exceptionalism is justified when it works – but ours is not working.

Design codes are part of a process that more and more people the the left and right now support, a process of “bringing democracy forward” and setting clearer, more readily comprehensible and more visual quality asks locally so that a wider range of providers can create more homes and better places.

In time, design codes will also be more readily digitalisable so that people can more spontaneously and cheaply see in advance what they can and cannot build: to understand what is acceptable locally and the “fast track” to development. Indeed, this is already starting to happen, with hopeful early results.

So, are design codes a panacea? The real world does not have panaceas. Will there be challenges? Of course, there will.

But, from what I am seeing so far, I dare to hope that, done well, design codes will set clearer, more popular local quality standards and reduce risk for good, beautiful and sustainable places.

If we learn more efficiently and effectively to channel public preferences into our local plans, then design codes can also start to re-forge the trust that, as a statement of statistical fact, the public has lost in our ability to create new places that cherish and improve the old.

To councils seeking to create codes I would say: do have a look at the Office for Place’s new online library, which sets out some of the best case studies to date. It is still modest but will grow in months and years to come.

And do have a look at the 10 criteria for effective design coding which the Office for Place has set out. Above all, keep codes short, visual and numerical and find out what people really like.

Nicholas Boys Smith is founding director of Create Streets and chair of the Advisory Board for the Office for Place

The Building the Future Commission

The Building the Future Commission is a year-long project, marking Building’s 180th anniversary, to assess potential solutions and radical new ways of thinking to improve the built environment.

The major project’s work will be guided by a panel of 19 major figures who have signed up to help shape the commission’s work culminating in a report published at the end of the year.

The commissioners include figures from the world of contracting, housing development, architecture, policy-making, skills, design, place-making, infrastructure, consultancy and legal. See the full list here.

The project is looking at proposals for change in eight areas:

- Education and skills

- Housing and planning

- Energy and net zero

- Infrastructure

- Building safety

- Project delivery and digital

- Workplace culture and leadership

- Creating communities

>> Editor’s view: And now for something completely positive - our Building the Future Commission

>> Click here for more about the project and the commissioners

Building the Future is also undertaking a countrywide tour of roundtable discussions with experts around the regions as part of a consultation programme in partnership with the regional arms of industry body Constructing Excellence. There is also a young person’s advisory panel.

We are inviting readers to submit ideas for how to improve the built environment through our online form which will form part of our Ideas Hub.

Postscript

]

No comments yet