A Boston restoration project using advanced 3D-modelling and printing technologies could hold the key to a new age of decoration within contemporary design

When most people try to relate BIM to buildings, they will probably think of modern architecture. The amorphous parametricism of Zara Hadid or the chaotic deconstructivism of Frank Gehry seem like the most natural bedfellows for the pioneering geometric complexities that digital processes allow. But what if BIM helps to push the boundaries for more traditional architecture? And what if it unwittingly leads to the resurrection of an architectural discipline dismissed and reviled by modernism for almost a century: decoration?

This is exactly what is taking place on a cosmetically dilapidated Edwardian university building in downtown Boston, US. The 12-storey Emerson College Little Building was built in 1917 as an office block. In 1994 it was converted into student housing and it is today home to almost 1,000 students. Local practice Elkus Manfredi Architects has just begun an extensive renovation aimed at increasing internal floorspace and restoring its weathered facade.

The facade in question (pictured) is an elaborate Edwardian frontage complete with all manner of ornate detailing. This includes finials, pinnacles, volutes, entablatures and statuary all intricately carved from pale Indiana limestone. Over the building’s 100-year history, the quality of this decoration has deteriorated and much of the stonework has been left decayed, with several ornamental details having fallen off.

But a 3D-modelling and printing project is under way to bring the facade back to life.

The restoration project has been progressed by both architects and contractors from Suffolk Construction working from software giant Autodesk’s BUILD Space, a high-tech workshop for the construction industry based in the company’s Boston Harbour headquarters.

Thomas Carrier, 3D fabrication coordinator at Elkus Manfredi, explains: “The plan is to restore the Little Building as closely as possible to its original composition using advanced technologies in ultra-high-performance concrete panels. The work focuses on utilising additive and subtractive manufacturing technologies to create visual mock-ups that serve in analysing the recomposition of the facade from point cloud data.”

Process

As Carrier indicates, the process starts with a point cloud survey of the existing building facade. This is completed using a combination of ground-level capture and hand-scanners on scaffolding. A Revit model of the existing facade is then created from the collated data, which provides a 360-degree representation of the building’s architectural detailing.

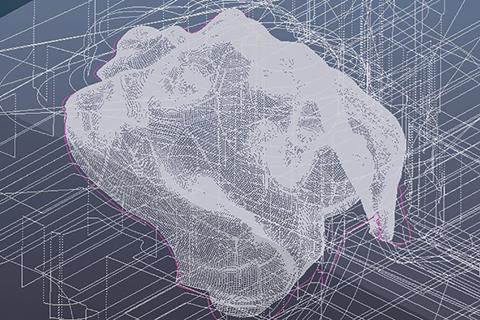

Using the model, the designers are able to digitally sculpt new decorative details directly extruded from the geometric composition of the facade’s original ornamental features. Existing decoration is identified as a series of 3D-meshes, which Carrier explains forms the basis of an onscreen “digital sculpting process” that creates new decorative features to repair or replace damaged ones.

Once this process has concluded, the files are sent for the digital fabrication process to begin. Fabrication now takes two forms. At Build Space, CNC laser-cutting machines digitally print 3D high-density polyurethane foam models of these decorative features using subtractive printing techniques. This is a process whereby 3D objects are constructed by successively cutting away from a solid block of material.

Carrier describes this period as essential. He says: “It allows us to refine the decoration and physically carve away at the model to achieve the optimum decorative form. Crucially, it also allows us to easily create mock-ups at numerous scales that can be presented to various parties, such as the City of Boston, for discussion and approval.”

Once the design is agreed, additive 3D printing techniques will be used to cast 1:1 scale ABS thermoplastic moulds of the decorative features. Fibre-reinforced pre-cast concrete will then be poured into these moulds ready for installation on the renovated building facade as the finished decorative features.

Potential

For Carrier, the new technology is a win-win. “As our contractor has pointed out, it boils down to the fact the pixels are cheaper than bricks. While it is difficult to quantify the exact project cost savings due to the infinite amount of variables, the ease with which we can create visual mock-ups enables the team to analyse complex geometric intersections, inspect areas for water infiltration, gain a clearer understanding of the recomposed decorative features and essentially avoid costly construction-related enquires before installing pre-cast concrete facade panels in the field.

“The previous way of doing something like this would have been a lengthy design and submittal process during which there would have been an enormous capacity for misunderstanding and misinformation.”

Carrier does not merely see this process as solely related to project management but one directly invested in the principle of decoration within architectural design.

“It gives us a new line in ornamentation. Material-wise, the possibilities are also endless. At Boston, we’ve used concrete as the final material but as the design is based on digital files, there are universal CNC fabrications which could digitally produce decorative features made out of timber, resin, plaster or one day soon maybe even glass.

“This is not just a technological process. The more we can do digitally, the more successful we’ll be at creating architectural objects with greater craft and precision.”

Here in England, one architect that knows more than most about the roots and principles of architectural decoration is Robert Adam, co-founder of Adam Architecture. While renowned as one the UK’s foremost practicing exponents of classical architecture, Adam is unequivocally convinced that embracing BIM and its 3D-printing possibilities holds the keys to a new age of decoration within contemporary design.

“This new technology is potentially game changing. I’ve been fascinated by 3D-printing capabilities for some time, but no one has quite grasped the impact yet of what it could mean for design.

“While traditional moulds are expensive, the cost of digitally producing special profiles isn’t, and this offers amazing possibilities for the ease with which decorative features can be produced.

“So what people are suddenly faced with is the opportunity to use ornament but in a completely new and different way to how it was created before. It’s a development that I don’t think many people really expected – architecture like Zaha Hadid’s and parametric principles are perhaps the more obvious product of digital design and fabrication.

“But now we have proof that decoration no longer has to be traditional, it can respond to current technology and potentially be designed to look like anything that can be printed digitally. That’s potentially revolutionary.”

However, Adam foresees potential obstacles. “While this fits into the ideology of architecture responding to technology, of course it doesn’t fit into modernist architectural dogma which is still locked into its anti-decoration stance.

“But right now I see architecture as being in a transitional period. I think resistance to decoration is less shrill than it used to be and there’s a general broadening of architectural perspectives. We could be at the beginning of a new modern era where architectural decoration is finally given a chance.”

Reservations

What Adam describes as dogma is still strongly in evidence across the architectural profession and there are some who are more cautious about viewing 3D-printing capabilities as the start of a new era of architectural decoration. Peter Inglis is practice leader at Cullinan Studio and he admits to “not being particularly interested in intricacy or decoration per se”. For him, the possibilities presented by this technology are more about customisation rather than decoration.

“The flexibility inherent in digital techniques of manufacture will allow for greater customisation, as the cost difference between standard and bespoke reduces. Manufacturers who have moved towards just-in-time-type systems, manufacturing everything to order rather than holding stock, are already working this way.

“One great advantage is the ability for the architect to model an element digitally, send the model to the manufacturer, and then have the manufacturer’s digital model, optimised for production, slot back into the main model, allowing for better coordination.”

Inglis also takes issue that one of the biggest inhibitors of decoration is the loss of skilled craftsmanship and argues that this craftsmanship is simply being channelled in non-manual forms.

“There is a bit of romanticisation going on about the loss of skilled manual craftsmen. The skills and knowledge needed to know how to get the best out of modern digital machine tools: what can be achieved and what can’t is as specialised and skilled as those of manual techniques.”

One architect who is renowned for using decoration within a contemporary idiom is Eric Parry, but he too is cautious about the decorative potential new 3D-printing technology holds.

“While I’m not a BIM user myself, we use it extensively within the office and it is undeniably brilliant as a common platform for coordination and efficiency. But as a tool for creating detailed architectural decorative design, I see it as limited and not sensitive enough.

“So much about decoration is about instinct and initiative. Patterns and geometry require a critical appreciation of scale, jointing, tessellation, ceramics, radii, grounded edges. In short, they have a sculptural quality which relies on critical experience and intuition. Programmes can help enable this, but they can’t generate it.”

It remains to be seen whether BIM and 3D printing are set to resurrect a centuries-old architectural tradition that has spent the best part of the past 100 years out of favour. But it would mark a stunning irony indeed if the old decorative craftsmanship that built Emerson College Little Building and its ilk was revived by the new technologies being used for its restoration.

No comments yet