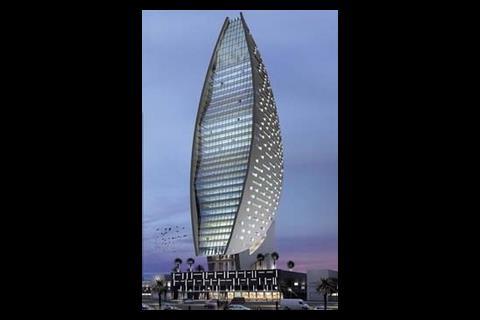

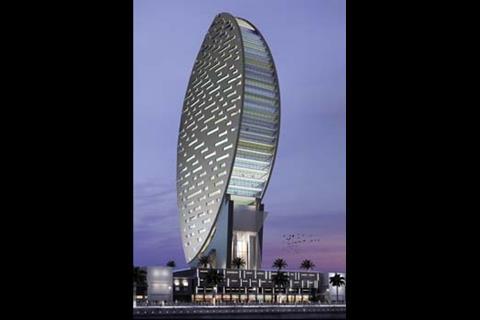

Modern architecture and vertiginous height is no longer sufficient to get noticed in Dubai. Stephen Kennett discovers how the newest addition to the skyline will make its mark

How do you make your office stand out in a city that is already brimming with architectural icons? That was the dilemma facing Indian developer Sheth Estate International when it purchased three adjacent plots of land in the Business Bay district of Dubai. This city is home to the world’s first – albeit self-appointed – seven-star hotel, the Burj Al Arab; the world’s biggest shopping centre, the City of Arabia Mall; and the Burj Dubai, currently rising at the rate of a floor per week and will be the world’s tallest building when it’s completed in 2009.

The answer is surprisingly simple – you build what Karl Hurwood, senior mechanical engineer at Atkins, terms a green office. From a UK perspective this sounds unoriginal – and, indeed, by standards over here the building would hardly pass muster as an eco-conscious project, probably only just scraping 2006 Part L requirements. But compared with the Middle Eastern norm of a fully air-conditioned glass tower, it breaks the mould.

“In Dubai, because of the timescales given for projects, there is quite often not the creative drive to make buildings as green as they perhaps could be,” Hurwood explains. “Our aim was to try and improve the efficiency without any extra cost, and we’re aiming for around a 20-35% reduction in energy use, compared to a standard Dubai building.”

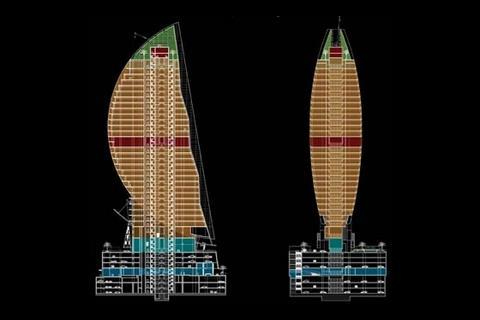

The multi-tenanted Iris Bay development will also be eye-catching. In profile, it resembles a crescent moon, balancing on a slender base above the podium levels, beneath which lie seven storeys of underground car parking and ancillary spaces. The double curved, ceramic-coated east and west elevations sandwich 36 floors of office space between them.

These are divided into a series of smaller units, typically 100-150 m2. It’s what is referred to as the “one man and his fax” approach in Dubai, where the majority of offices are let to small businesses, and anyone wanting a bigger office simply takes down the dividing partitions.

One of the initial challenges for the environmental designers was the positioning and amount of glazing in the building. “Everyone in Dubai wants fully glazed buildings,” says Hurwood. “What we’ve tried to do on this job is to look at the site and consider the best place to put that glazing.”

In answer to this, the fully glazed façade faces almost north, cutting down on solar gain and glare. The plan is that this façade will have thin film photovoltaics integrated into the laminated glass, as the sun is very high in Dubai and it will receive a lot of sunlight in the summer months. This has yet to be given the go-ahead, partly, says Hurwood, because it would be a premium to the building’s cost and also because local authorities are reluctant to give approval to systems that will connect in parallel to the main incoming supply.

The other heavily glazed elevation points south, but this is fully self-shaded by the balconies on each floor, and by the east and west elevations that project clear of the south-facing façade by up to 6 m at their most prominent points. “This approach might sound obvious, but is rarely the case in Dubai,” says Hurwood.

Where the potential for solar gains is high, on the east and west elevations, attempts have been made to reduce the glazed areas. Windows – some up to 8 m x 3 m – are punched through the ceramic-covered cladding to coincide with the office spaces inside.

The planning authority felt the continuous north-facing façade at the front of the building should not be broken by plantroom louvres, so all of the building’s main intakes and exhausts have been hidden by incorporating them into the inside faces of the projecting east and west elevations. “This gave us an intake plenum we could use to feed our main ventilation plant. The same was repeated on the rear elevation for the exhaust louvres,” he says.

With outdoor temperatures in Dubai peaking at about 48ºC and high humidity levels, full air conditioning is a prerequisite. The building has a projected cooling load of about 6.5 MW and, as is increasingly the norm in Dubai, this will be provided by the local district cooling network.

This works on a 9ºC delta T, with chilled water delivered at 5.5ºC and returned to the circuit at 14.5ºC. “Under the district cooling act, there are a lot of penalties if you don’t return your water at certain temperatures, so basically it doesn’t matter what flow rate you take, you have to maintain the return temperatures, and if it drifts more than 0.5ºC, they start fining you,” says Hurwood.

This restricts what can be done to reduce energy consumption on the primary side, and so the design team has aimed to improve efficiencies elsewhere. Significantly, variable speed pumping will be used in conjunction with differential pressure control valves.

“Differential pressure control valves are rare here in Dubai, so good control of a variable speed circuit is not often obtained,” he adds. “This means most buildings tend to run OK at the design load, but struggle to give full control over part-load cooling.”

Commissioning is also made easier by the differential pressure control valves. This is significant, given the expected high churn rate . Over the course of a year, it would be typical for 20-30 of the 250 offices to change tenants. The differential control valves and constant air volume dampers avoids having to rebalance every office on a floor when significant changes are made to others.

These will be installed as prefabricated modules as part of the bid to push up the quality of construction on the project and get around the shortage of skilled labour.

Unusually for Dubai, construction has begun without the majority of tenants signed up, showing just how confident Sheth is of its appeal. Completion is due in November 2008.

Downloads

Fig 1

Other, Size 0 kb

Source

Building Sustainable Design