Mechanical services engineer Morwenna Wilson found that the best way to inspire schoolchildren to consider a career in construction is to build structures out of food

I spent my entire school life in single-sex education, so the careers advice I received was limited to the usual suspects: law, medicine, education. But with the support of my parents and friends, I managed to break the mould and now, after only 18 months, feel very much at home in my job as a mechanical building services engineer. Armed with first-hand experience of the restricted choices that may be presented to teenagers, I decided to try to encourage more young people to venture where they might not have already been inspired to go – into a career in the construction industry.

With the backing of my employer, Arup, I worked with Judy Hallgarten from Camden Education Business Partnership to organise a day of workshops at Camden School for Girls in London. The date was arranged to coincide with National Science and Engineering Week from 9-18 March.

My previous workshop experience came from managing Engineering Extravaganza, a London event that was a small part of Arup's contribution to the Open House weekend in September 2006, for which buildings across the country were opened to the public for viewing. The two days of interactive demonstrations were designed to give children (and enthusiastic adults) an insight into engineering in the construction industry and illustrate that much more than architecture goes into creating a building.

As well as demonstrations that ranged from the damping mechanisms used on tall buildings to the workings of toilet cisterns, two practical activities proved so successful that I suggested using them for the school workshops.

I would have preferred one of these to be services-related – the advantages of thermal mass or misting fire suppression systems, for example – but such demonstrations could not be done in a couple of hours. Nor could they be realised using everyday items, which I thought necessary to help the children warm to the industry. In my mind the most important message to convey was that engineering is centred on creating designs to solve problems.

At the beginning of each of the workshops, my colleague Alice Tedd and I talked to the 13-14-year-old students about the choices we had made for our further education, what a normal working day entails and why we had been attracted to the construction industry. Although working on interesting buildings and the opportunities for travel rank high on the list of advantages, the main selling point for me, which I wanted to share with the children, was the pleasure I get from working with such a large number, and variety, of talented people.

Dropping hints

The first activity was ‘the falling egg’. The 20 groups of five students were each given an egg, and asked to ensure it would not break when dropped from a second-storey window. (Admittedly, they were hard-boiled to help reduce the burden on the school cleaner.) I explained this was not the sort of task I carried out every day, but that a vast array of engineering specialisms bore some similarity. For example, Arup carried out a groundbreaking study for the Central Electricity Generating Board into the impact behaviour of a Magnox nuclear waste transport flask. As well as a train crash test, this required full-scale and scale model drop tests, non-linear finite element simulations, transport risk assessments and a study of damage in real target impacts.

I had planned to give the winning team a prize of chocolate, but in the pressure of the moment this slipped my mind. I’ll admit that standing in front of 100 children, not knowing how they are going to respond, was possibly even more nerve-wracking than having to do a presentation in front of superiors at work. Luckily, as it turned out my chocolate bribe would have been wasted because the students were wearing very large grins and some were even clapping their hands with excitement.

Their first 20-minute session was for brainstorming, taking into consideration the time constraints and the materials available. The pupils were told points would be awarded for an unblemished egg, innovation, an easy-to-open package, manufacturing quality and, most importantly, teamwork. With their designs now on paper and equipped with card, scissors, sticky tape, string, plastic bags, a small amount of bubble wrap and balloons, they enthusiastically began to manufacture the packages. The look of guilt on the faces of the individuals who had been popping the bubble wrap while waiting for the activity to start was obvious even from the opposite end of the room.

The teachers, support staff, Alice and I tried to lead the groups through the thought processes necessary to achieve a successful design. With so many groups and only 50 minutes, this was hard, but the room soon became a hive of activity, with good ideas spreading quickly. Although the technical explanation behind the ideas may not have got through to every individual student, most finished designs proudly displayed parachutes and crumple zones.

Testing of the protective packages seemed to provide the greatest excitement, with loud ‘ooos’ and ‘aaahs’ for the ones that crashed with a bang even a bouncy ball would have been lucky to survive. But among the 20 groups there were only six breakages.

Once we had managed to convince the students to sit down and stop examining each other’s successful or disastrous creations, each group presented an A3 poster to highlight the most important and impressive features of their design. Hopefully it was beneficial to them to practise standing up and talking to a large number of people. I know it had been for me an hour earlier.

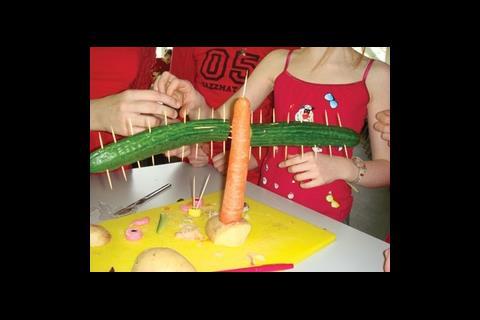

The second of the activities was titled ‘edible structures’ and was carried out with a single class of 30 students. Each group of five was presented with a structure, such as the Millennium Bridge or the Angel of the North, and was asked to construct a small imitation using food. They were provided with a list of construction materials, which included cucumbers, carrots, potatoes, spaghetti, biscuits, sweets and cocktail sticks. To try to replicate the constraints of the construction industry (and to discourage the students from eating their work) each item had a cost and there was a total construction budget for the building.

Budget lessons

Alice and I encouraged the students to carefully consider which foods were most appropriate for their structure and how many of each item they required. Although they could choose from food items that totalled £54 million, they only had £42 million to spend. Any items bought after the first round of purchasing (due to miscalculation) were charged at a more expensive rate. Wastage of material during construction was also taken into account.

To my surprise, the students were extremely confident when they approached us with their lists of materials and associated costs. Hardly any of the groups initially intended to spend more than £35 million. Construction then started feverishly. The groups that had not taken our advice to sketch their structures to show where the food items would be used quickly ran out of materials or squabbled about how to complete their designs with limited resources.

With a smaller number of groups working on this activity, Alice and I could spend time with all the teams and discuss possible improvements to the design or how they felt they could have tackled the activity better. In this respect I felt it was a thorough learning experience, where they were prompted to think critically and had the chance to learn from their mistakes.

Full of imagination

Although some of the structures ended up a little over budget after a second phase of purchasing, the results were fantastic. The imagination of some students was far beyond anything I’ve seen in a long time and was a real inspiration.

Before taking any credit for the ‘edible structures’ idea, I should acknowledge that it was run as an internal competition at Arup in 2004. At the time the entries ranged from a delicate carrot and courgette bridge over a spaghetti river, to a jelly swimming pool complete with waffle diving board and red liquorice lane dividers, and a solitary gherkin for 30 St Mary Axe in the City.

I am organising another day of workshops to coincide with National Construction Week, 8-12 October 2007. Having received interest from nine secondary schools in Camden, Judy Hallgarten and I are hoping to bring together small groups from all of the schools to run a combined workshop.

Students who were in the Camden School for Girls workshops have asked me for engineering degree advice and information on work experience. It appears I may have genuinely influenced the future direction of some young people’s lives and made a small contribution to the potential growth of the construction industry. I’d say that was a good day'’s work.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

Morwenna Wilson is a graduate mechanical engineer with Arup

No comments yet