Maccreanor Lavington has given a tired Victorian school a public face and facilities suitable for modern teaching method, without compromising its original character or surroundings

For all the good it undoubtedly did, one of the more unfortunate legacies of the quashed Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme was its tendency to view design quality as a direct consequence of building cost. This has led to a generation of lavishly and conspicuously reconfigured school buildings where the primary focus appears to have been on big and brash new architecture – rather than an empathetic design response attuned to the needs, character, culture and fabric of the particular school building and its site.

While the subsequent drive for standardisation as evident in the successor Priority Schools Building Programme (PSBP) has certainly removed the emphasis on extravagant cost, it does not necessarily prioritise high-quality architecture either.

Which is why it is so refreshing to come across a new school that eschews both the brash exhibitionism of BSF and the dour regimentation of PSBP to devise an inspiring design solution, based on a number of modest yet highly effective design interventions. The result is a thoroughly rejuvenated school campus that applies a contemporary new face to a formerly tired and inefficient school building.

Primary school expansion programme

Grange primary school near Tower Bridge in London has been designed by Maccreanor Lavington Architects. The scheme expands the school, allowing it to increase its entry numbers from about 45 to 60 each year. It is part of the London Borough of Southwark’s radical refurbishment and expansion of primary school places and has transformed the south London borough into a leading public patron of contemporary school design. Accordingly, the borough itself now plays host to works by some of the country’s most renowned educational architects, including Haverstock, Cottrell & Vermeulen Architecture and Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios.

Prior to its refurbishment Grange primary school was a typical three-storey block in the Victorian state school tradition, with a playground and separate school caretaker’s block beside it. Like many schools of the same ilk, it exhibited a number of problems. The caretaker’s block was riddled with damp. Classrooms had become tired and worn cosmetically, while their cellular layout also made them increasingly inefficient and inappropriate for modern teaching methods.

Additionally the school did not have a single hall capable of accommodating an entire school assembly. Instead, it had three separate smaller halls on the first floor of the main building – far from ideal in terms of both usage and accessibility. From an urbanistic point of view, the school’s most conspicuous drawback was that it had virtually no street presence whatsoever, because the main school building was set back from the street and blocked by the caretaker’s block and a surrounding high brick wall.

These challenges formed the conceptual nuggets of the new scheme. “The first thing to do was to give the building a street presence,” explains Maccreanor Lavington associate Tom Waddicor, “but we didn’t want it to be a bolt-on extension to the existing building and nor did we, or the planners, want any new block to block the view of the original school building.”

New street frontage

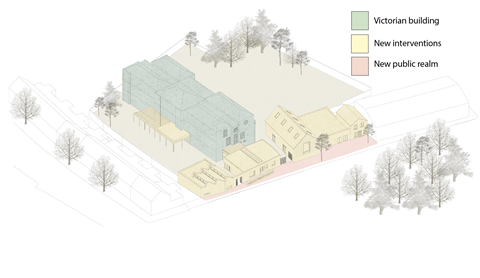

The solution is a radical one. The street-facing caretaker’s block and adjacent high brick wall have been demolished. In their place, a new continuous single-storey building has been constructed along the entire street edge, directly facing the road across a widened pavement and providing the civic presence that the school previously lacked.

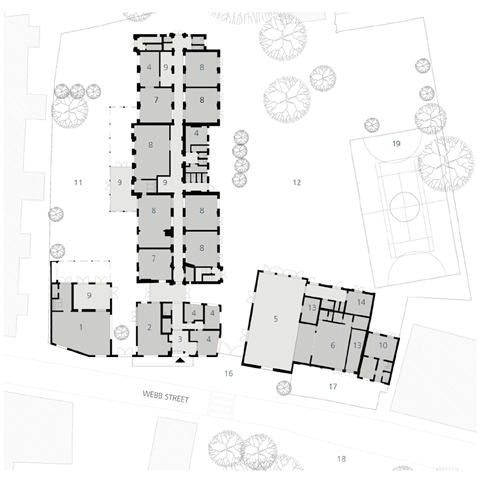

In functional terms, this new linear block ties various disparate uses together. At one end is a new nursery, beside which sits the new main school entrance and then after that an administrative area containing offices. Next comes a new gated entrance to the playground beyond, and after that the gable end and pitched roof of a new school hall. Finally, on the other side of the hall lies the new caretaker’s house – the only part of this new block that extends to two storeys. The main entrance is the only part of the new annexe that touches the main school block.

The entirety of the new annexe is faced in a pale, wonderfully textured version of trademark Maccreanor Lavington brickwork, a material that Waddicor rightly claims is “synonymous with the area” and one that he honestly identifies as being in place simply because Maccreanor Lavington “loves bricks”.

The pitched-roof hall is the volumetric highlight both inside and out, providing a space big enough to hold a whole school assembly and capable of being leased for community or commercial hire – a welcome new revenue source. Aesthetically, its pitched roof punctuates the otherwise flat annexe roofline and provides a sense of the folksy communality one associates with barn dances, village halls and, on occasion, the more amenable permutations of inner London backstreets.

Inside the new block, new spaces are topped by rooflights to minimise windows and thereby ensure privacy along the new street frontage. The annexe is almost exclusively lined in cross-laminated timber which, accordingly to Waddicor, offers numerous familiar advantages, such as speed of construction – “the internal fit-out was completed two months early”.

He adds: “We were also cautious about the cost and durability of applied finishes, as this is a robust and hard-wearing self-finished structure. The additional comparative cost of using [cross-laminated timber] was offset by the fact we didn’t need to apply an additional finish on top. Plus it gives internal spaces a real sense of texture and warmth.”

As a solution to the school’s problems, the new annexe is a modest masterstroke. While providing a new hall and additional accommodation, it also manages to deliver a

level of integration with the local urban grain that was previously absent. Keeping the block as primarily a single-storey volume ensures it does not block views of the main Victorian school beyond (a key planning requirement) and even accentuates the older block’s impact by visually framing it with the pitched volume of the new hall to its side.

Adaptations to the original block

This project was presented initially as a number of modest interventions and, while the new block is the biggest of these, the other components lie in careful adaptations to the Victorian block. The decision to build a new hall and administrative block rather than new classrooms was significant. “We really didn’t want to build a new classroom block,” explains Waddicor. “Crossing the playground to reach the hall felt fine, but the separation of a new classroom block felt wrong.”

Consequently, the interior of the main block has been radically rearranged. The double-height first-floor halls have been halved in height to form single-storey classrooms. New classrooms and teaching areas have been placed on the side of the block away from the main playground to provide the quiet required for lessons. And the former cellular arrangement has been reconfigured into clusters of two 40m² classrooms with a 40m² satellite space used for informal teaching or break-out areas.

The really interesting aspect is that despite revolutionising the way in which the building is used, these measures are incredibly light-touch. With the exception of the new floors subdividing the former halls, “it’s all just joinery”, says Waddicor. So much so that it was a joinery subcontractor that completed the works within the main building, as opposed to the main contractor that built the annexe.

But despite these works being lean in nature, they make a significant point about school rebuilding. For they prove that improving school buildings is not about extravagant statement architecture but more so about understanding the nature of the building fabric and its problems and devising an intelligent architectural solution that responds first and foremost to these.

Yes, the innate physical assets of the Victorian board school typology certainly help: with their spacious rooms, high ceilings and huge windows offering copious amounts of natural daylight and ventilation, these building clearly offer manifest advantages that even the most incompetent refurbishment would struggle to quash.

But the annexe is clearly not conceived as an alternative to the main school but as an adjunct to it, and as a consequence its procurement has wisely not been allowed to deflect attention away from the core spatial and functional needs of the main school block. That all these interventions have managed so radically to improve the way in which the school is used, while being delivered with such efficiency and cost-effectiveness, provides a humbling lesson that could be applied to all architectural solutions. They also give truth to what Waddicor describes as the central, overarching design approach of the entire project: “Identify the character of the school and don’t fight against it.”

Project Team

Architect: Maccreanor Lavington

Client: London Borough of Southwark

Main contractor (new build): Morgan Sindall

Main contractor (refurbishment): Graeme Ash Shop Fitters

Project manager: Mace

QS: Keegans

Structural engineer: Waterman Structural Services

Building services engineer: Waterman Building Services

Landscape architect: Wynne Williams Associates

Cross-laminated timber subcontractor: B&K Structures

No comments yet