Eventually, we begin to realise that all these interdependencies are interconnected. We share the same limited resources. We achieve most when we are all successful and we loose most when we all fail. Whatever you call this, perhaps highest level of awareness, it is rarely attained by individuals and is sorely missing in the world at large.

This growth cycle is not just about individuals; it also applies to communities, businesses and industries. It was this growing awareness which, following the merger in 1995, lead the newly formed Glaxo Wellcome to pilot an alternative approach to construction activity.

Called Fusion, this was a collaborative approach based on fundamental team values of fairness, unity, seamless(ness), initiative, openness and no blame. The approach initially evolved during the major redevelopment of one of the company's laboratory buildings at its Ware research and development site in Hertfordshire, before being applied from inception on the restructuring of the Beckenham site in Kent.

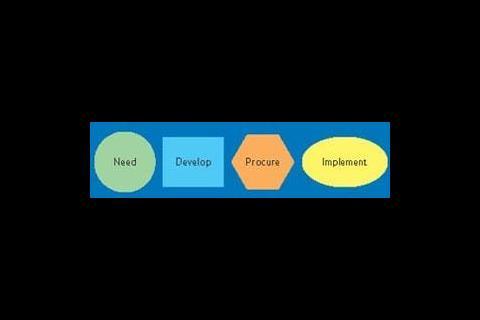

The traditional process

The traditional way of undertaking a project is to assemble a team of designers to consider the business needs and to investigate the feasibility of a solution. This design team, normally supported by quantity surveyors, then develop a scheme outline and detail designs, which are used to procure the implementation team of contractors, suppliers, manufacturers and others.

The isolated components of the implementation teams are then asked to tender against the design drawings. Usually this is the implementers' first sight of the drawings and in the limited time on offer they make assumptions about the intent, misunderstand some of the content, make mistakes in translating their supply chain's proposals, offer alternatives which are not really equivalent and often make flawed commercial decisions about how and where profit will be made. They generally hold back their concerns about the detailed proposals as experience shows that designers tend not to recommend appointment of people who criticise the design. Despite the best endeavours of the selection team many of these problems cannot be identified in the appointment process. However, once the contracts are let, the implementation team comes together and voices its concerns, suggesting different solutions and pointing out the weaknesses and inconsistencies in the design drawings and specifications.

Why does all this happen? Quite simply because the concept of asking a group of people who don't do implementation to develop solutions for another group who do, but without consulting the implementers in the design process, is fundamentally flawed. It leads to a lack of ownership and buy-in with the all too familiar consequences: misunderstanding, disagreement, conflict, abortive work, delay and in the worst case claims and liquidations. No wonder the outcomes are frequently sub-optimal and in the extreme not really fit for the purpose for which they were originally intended.

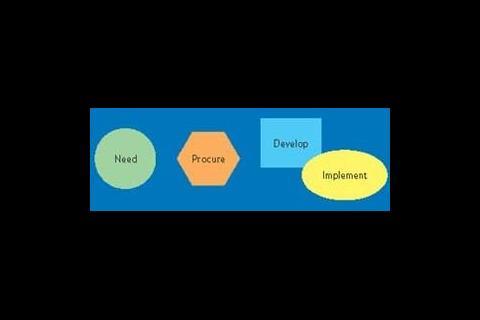

The Fusion approach radically re-engineered this process. The starting point was still the identification of the business need. Initially this was the disposal of the 40 plus hectare Beckenham research and development site after the functions housed there had been relocated to sites in Greenford, Stevenage and Ware. As the project developed it was clear that the biotechnology functions would be prohibitively expensive to re-provide elsewhere. The need to consolidate biotechnology onto around 10 hectares of the site became the starting point for the restructuring project. A small master planning group was assembled to assist in developing the high level plans and an indicative budget. Once this 'scale' work was completed an appropriate team with the necessary capabilities to handle the project at the scale identified was assembled.

This assembly was a progressive activity. First the space planners were selected and appointed. They joined the selection teams to appoint services and civil/structural engineers who joined the team to appoint a builder, who joined to appoint a mechanical contractor and so on. In all, ten primary partners were appointed (not all interviewed by everyone, the expanding team agreeing who should be included in the selection panel). All the primary partners were contracted direct to Glaxo Wellcome, including a laboratory furniture manufacturer and a communications systems installer as both were considered critical to the project's success. Appointments were made on an open book basis, meaning payment would be made on the actual cost of goods and services provided with an agreed mark-up for overheads and profit. Common commercial terms were applied which had no provision for set-off and liquidated damages were set at zero.

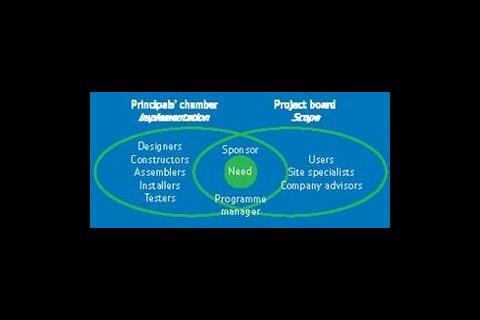

There was no main or managing contractor appointed, instead a principals' chamber was formed comprising the ten primary partners together with Glaxo Wellcome. This chamber provided equal status for the principal members of the primary partners to agree the principles of the project. Chaired by the project sponsor, the principals' chamber was assembled at the onset and its first activity was to agree who should do what. Roles were allocated to those best suited irrespective of which company they came from. The project team was assembled under a programme manager who was also a member of the principals' chamber and the primary conduit to the project team.

The Fusion process

A quick start process was introduced with an off-site team building workshop. All the key members of the project team were assembled to gain an understanding of collaborative working as described in Fusion, to explore each other's roles and responsibilities and to reach common agreement on the goals and objectives. At this workshop the team agreed a charter, a project logo and a three statement value proposition. This was:

- Scope – a realistic solution to the business requirement.

- Programme – optimise time, maximise opportunity, realise success.

- Cost – input partnership, output value.

The project team was then ready to investigate the high level plan, the target budget and to develop a detailed scope and cost plan for the project. Now the radical differences of Fusion became clear. The team are free to decide how much time and effort is needed to be expended on design, including who is best to undertake that design and how much design is necessary before manufacture, assembly and installation should progress. There were no approved design drawings to be 'handed off' and turned into working drawings by someone else, merely to apportion accountability (blame) at a future date. There were only agreed fabrication/installation drawings reflecting what was actually to be implemented, to be updated as work took place and become as-installed drawings that actually reflected what happened. In this way design is able to proceed as a bow wave ahead of installation, with the team deciding what 'gateway' decisions are needed at what point in time and leaving details to be defined when they are required. With all the primary partners involved in the designs and decisions that affect them most, there is buy-in and ownership of the outcomes and most problems were identified and resolved while they were still on the drawing board.

Of course this process was new and there were misunderstandings and differences of opinion. There were also problems which made their way onto the site in the guise of co-ordination clashes, delivery and availability issues, quality control and the inevitable spectre of changes and variations. The ways in which these were resolved go further to illustrate the radical changes delivered by Fusion.

At Beckenham the site operatives were empowered. They were authorised to stop if they found a co-ordination clash. They were also permitted to suggest alternatives and to call in the design team if they needed advice or if the change was outside their level of expertise or required evaluation of the impact on other trade activities or design parameters. They were also empowered to seek other workfaces while the issues were being resolved or paid for standing by if there were no alternatives available. Consequently the amount of abortive work at Beckenham was dramatically reduced leading to significant savings in material and man-hours. Furthermore, the commitment of the workforce remained high and a steady stream of suggestions and ideas for improvements flowed from the workface.

Everyone involved

Not that this happened by chance. Every person joining the project was given an induction into the Fusion values and was explained the project goals and objectives, what they meant and why they mattered to Glaxo Wellcome. This philosophy extended throughout the project team and everyone was encouraged to use their initiative.

Occasionally people would make mistakes and these were rectified without penalty and treated as learning opportunities for the whole team, provided they were not as a result of neglect or naive decisions for which people were expected to take responsibility.

This engagement and freedom to act was only possible because the boundaries which normally fragment the team were not permitted on the Fusion project. Everyone was considered part of the same team, encouraged to work across company boundaries and to challenge and question others to seek clarity and understanding as well as offer support and advice. By understanding that success could only be achieved if everyone succeeded, a culture of proactively seeking and resolving problems before they became critical could evolve. This was primarily a culture based on collective agreement, but of course it was supported by processes for escalating issues if agreement could not be reached.

Variations which would not significantly compromise the budget or programme were accepted and incorporated by the project team, whereas variations with significant impact were escalated. In the case of client changes there was an additional body formed to consider the effects of significant changes in scope. Called the project board, this body comprised senior representatives of the end user functions together with the project sponsor and programme manager.

To understand how these bodies interacted and how decision making could be effectively delegated without compromising the project budget it is necessary to understand the cost management process. Essentially it was the open nature of costing which was key to effective decision making. The budget was constructed as an elemental cost plan. In the early days many of these elements were unit rates based on previous experience, but as the project developed the costs were developed to reflect the detailed decisions made and additional information available. Costs for all necessary services and activities were defined, including client related costs such as planning approvals and building regulations. Contingency was agreed and identified for all to see and once the general scope was defined and agreed contingency allowances were allocated to the principals' chamber and the project board to deal with growth (design development and implementation related errors and omissions) and scope changes respectively.

In this way every member of the team was able to understand the implications of changes in their area on the overall cost plan and were able to make value based decisions. Furthermore, members were able to redistribute the budget to more appropriate areas as details were confirmed. The project board would review end-user proposals for change, considering the cost, time and feasibility advice provided by the project team, sanctioned where necessary by the principals' chamber. An end-user sponsor would be required to present the case for scope change to the project board which, if agreed, would be drawn down from scope change contingency. This process lead to buy-in to the budget from all parties and, not surprisingly, brought the project in both early and under budget.

Happy handover

The customer care team was responsible for ensuring that there were no major omissions and the end-users were not asked to confirm that the area could be accepted until they had used the facility for a couple of weeks and there were no outstanding issues. This lead to snag-free handovers and delighted end-users as the lack of pressure to agree to completion before occupation, and the time to get used to the new facility, eliminated many of the usual problems. This also delivered benefits to the project team as the snag-free methodology was supported by a policy of non-retention of contract funds.

A key requirement of the project was to consolidate GSK's biotechnology functions onto a corner of the Beckenham site, releasing the remainder for sale and redevelopment. The target budget for this consolidation was over £15 million. This required the 'unbuilding' of the 40 hectare plus Beckenham site which, like most sites, had grown with no consideration to future disposal (a good lesson for us all to learn if we are serious about sustainability). This means disentangling the services while maintaining the biotechnology operations throughout the 22 month programme.

The disposal strategy was to play a big part in this rationalisation as retention of part of the site as a science park or industrial or commercial business units would all significantly impact the services capacity and distribution methodology. This disposal strategy changed regularly during the project eventually ending up as a complete demolition and decontamination for resale as a housing site – although this was understandably resisted by Bromley Council who would have preferred to retain more employment. Despite this constantly changing backdrop the biotech formation project teams, as they decided to be called, delivered 20 infrastructure projects ranging from new security fence and protection systems to the diversion of surface water drainage running directly under the site. This was matched by 20 different facility projects, from restructuring existing laboratories and production suites to constructing new offices, boilerhouse and warehouse facilities. The nature of many of these facility projects was also changeable as the evolving Glaxo Wellcome biotechnology division was subject to organisational change during the early part of the programme, leading to variations in the sizes of functions to be housed on the Beckenham site.

With so much change the programme was a recipe for disaster, yet it was enormously successful, with each of the individual facility and services phases being delivered to an agreed sequence and schedule with very few sectional delays or overspends. This was because the various elements of the team worked in complete harmony. The project board was allocated only £80 000 for scope revisions, which they were entitled to augment by delivery of scope reductions. The principals' chamber had the lions share of the growth contingency, but at 7% of budget this was well below the level normally associated with a programme of this scale and uncertainty. The key to this was the open nature of the cost plan, which meant that at all times everyone could see how the various activities added together to deliver the target. Even the £15 000 given to the customer care team to be spent on whatever additions they agreed was visible to all parties and considered money well spent. This target did not overspend because in many ways it could not – it required everyone to agree to accommodate a change which could not be afforded, in order to produce an overspend. On the one occasion, (nearing the end of the last phase) when an additional business need arose that all parties felt would be of real value to Glaxo Wellcome, the function promoting the need refused to allow it to proceed if it would undermine the successful conclusion to the programme.

At the end there was 1% remaining in the growth pot which was divided equally among the partners who agreed at onset to a share risk/reward formula. The formula offered a maximum benefit of £50 000 per partner on underspend and a maximum penalty of £10 000 per partner on overspend. However, on the next and last major Fusion project for Glaxo Wellcome, the financial incentive was dropped. This was because all the partners felt that the guaranteed nature of profit and the opportunities – of being able to participate in such an enjoyable, rewarding and successful experience, for all levels of the organisation involved – made the financial nature of the incentives trivial by comparison. Indeed in some companies they decided not to face the dilemma of how to distribute the financial bonus to the project staff as it could undermine the relationships with other staff members not involved in such a pleasant project. As one of the principals put it: "I've got people who have to put up with contractual behaviour all day long asking why a colleague whose been working in a rose garden gets a pay out".

For GlaxoSmithKline the outcomes are far more than on time and under budget. The facilities and services delivered met and have continued to meet the evolving needs of the site because the team understood, really understood, what biotechnology was about and how it might change in the coming years. End-users were delighted with their facilities and felt valued by the way they were involved and consulted. Many of the partners continued relationships with GlaxoSmithKline transporting the lessons learned to other sites. At the post programme review (another feature of Fusion projects) the team compared the actual performance against their collective understanding of how it would have worked in a traditional (we must start to call this historic) model. They concluded that the work was completed 37% earlier than the traditional model would have allowed and permitted 21% of additional value to be added, which in traditional contractual relationships would have been lost to abortive work, rework and additional management resources. All of which demonstrates the power of fully integrated, genuine collaborative working which truly is altogether a better way.

Much of the learning from the Glaxo Wellcome Fusion project has been incorporated into the Strategic Forum for Construction toolkit on integrating the UK construction industry. Glaxo Wellcome merged in 2000 with SmithKline Beecham to form GlaxoSmithKline.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

Kevin Thomas was director r&d worldwide strategic planning at GlaxoSmithKline. He is now establishing himself as an independent coach, mentor and advisor to companies, teams and individuals who wish to adopt the industry changing agenda, through CWC Ltd and his own company Visionality Ltd.

No comments yet