High Speed 2 is a project people love to hate. But it would reduce train overcrowding, boost business and pump billions into the construction industry

High Speed 2 is one heck of a controversial scheme. The proposed 180km rail line - which would connect London, the Midlands and the north of England - has been the subject of fierce debate for over three years now. Critics have questioned its £34bn price tag, arguing it is too much to spend on a single infrastructure project, and local protesters have balked at the prospect of high speed trains hurtling through once-tranquil villages in the picturesque Chiltern countryside.

But for the construction industry it’s a very different story. Such a colossal project, and one that will span 16 years and employ 10,000 workers on the first phase of construction alone, promises much needed relief for an industry still reeling from the blows of the recession.

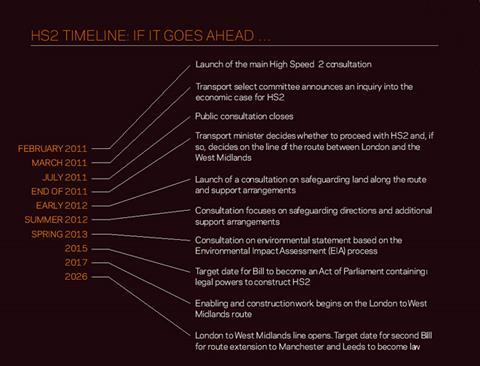

But will this megaproject go ahead? We haven’t got long to wait for the answer. The future of the scheme will be determined by late 2011, with all consultation due to complete in July. Following pressure from local MPs in towns along the proposed route who are opposed to the scheme, an inquiry into the economic case for HS2 was launched last month by the transport select committee. A full list of recommendations arising from this inquiry will be published and debated in parliament before the end of the year, and the final decision will be made in the next six months by transport secretary Philip Hammond.

As the crucial decision approaches, we explain how, despite concerns over cost and route, HS2 is one of the best solutions on offer for providing improved North-South links and increased passenger capacity. And we look at what £34bn worth of work could do for the construction industry.

Public debate

The good news for anyone hoping to work on HS2 is that, as the public consultation draws to a close and the financial inquiry gets under way, it looks increasingly likely that the project will go ahead. After all, the man charged with making the final decision is one of the scheme’s biggest supporters: “We can’t afford not to invest in Britain’s future,” says Hammond. “I want to tell the UK construction industry that this plan provides a visible 16-year pipeline of work. It will allow contractors the opportunity to consolidate their priorities and will be a big boost for the sector.”

And contractors are well aware of the benefits that this scheme could bring their way. Colin Stewart is project director for HS2 and global rail business leader for Arup, which was consultant on the project’s predecessor, HS1, and is developing the proposed route alignment for HS2. “The potential benefits of high-speed rail are proven,” says Stewart. “Take HS1, for instance; that line was a major spur in attracting over £10bn of regeneration investment, creating new quarters for London in Stratford and the King’s Cross area, as well as a new ’city’ in Ebbsfleet.”

David Booker, business development manager at Vinci Construction UK, adds: “HS2 is absolutely the right thing for construction. It provides an opportunity to maintain resources built up from Crossrail and to move them onto another scheme covering a wide range of disciplines.”

And Stephen Ratcliffe, director of the UK Contractors Group, says: “HS2 is good for the construction industry because it provides much needed work and jobs. It also helps the industry maintain its international competitiveness in building railways for the 21st century.”

Then there are benefits for the passengers. As the present rail network buckles under the strain of rising numbers, the prospect of less shoulder bumping makes HS2 highly attractive. Standard capacity on the line will increase by 50%.

Alison Munroe, chief executive of HS2 Ltd, a body formed by the government to oversee the scheme’s feasibility, seems convinced: “Users of the railway have doubled over the last 15 years and the trend is expected to continue. There is a very good case for building HS2.”

Peter Owen, managing director of Willmott Dixon in the Midlands, adds: “Speed and ease in getting from A to B remains essential to business. That’s why we rely on good infrastructure and it’s why the government is ploughing ahead with Crossrail and now plans to develop HS2. Birmingham is our second city and bringing it closer to London will attract more investment from multi-nationals, create more jobs and open up new business opportunities. As an industry, we’ll benefit both from HS2’s construction and the wealth it generates.”

The proposals

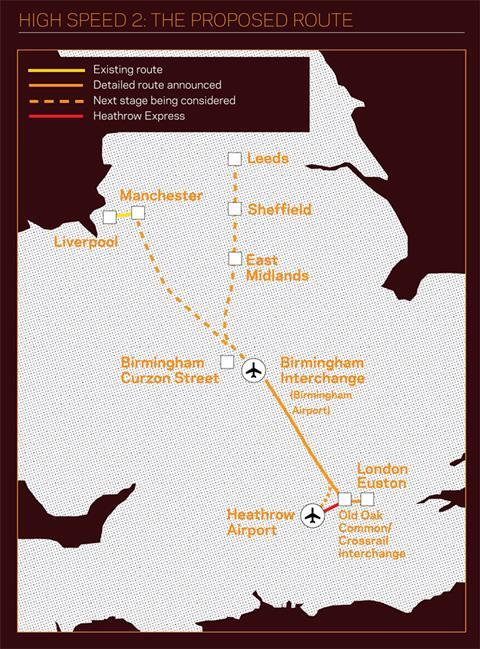

Under the scheme a spanking new rail network will link London, the Midlands, the north of England and, potentially at a later stage, Scotland. Phase one will cost £17bn, with construction work worth £7bn up for grabs. The first on-site works will be scheduled for 2016 and the government estimates that £44bn of economic benefits will be generated from phase one, which equates to £2.60 for every £1 initially spent.

From a commuter perspective, reduced journey times are a major advantage. HS2 passengers travelling from London to Birmingham will reach their destination in 49 minutes, shaving 35 minutes off current times on trains going at up to 225mph. If the second phase is approved, commuters from London will reach Manchester in a mere 80 minutes. Supporters point out that economic activity will also surge along the line where new stations are built.

Under the scheme a new station would be built at Old Oak Common in north-west London, Birmingham Interchange and Curzon Street. Euston station would also be expanded to twice its size. Tunnelling work would be carried out at Euston, Little Missenden, Ufton Wood, Chalfont and Amersham. Despite tunnels making up 13% of the route length, they occupy 23% of the construction cost. The combined station contracts are estimated to be worth £1.7bn, with the tunnelling contracts about £1.4bn.

Answering the critics

Despite the benefits the scheme would provide to the construction industry, valid concerns have been raised about the project, questioning how it stacks up economically and what it will mean for the towns, villages and countryside along the route.

The cost is certainly high. As HS2 involves the construction of a new line, the project is comparatively more costly than other European high speed rail schemes, which were built upon existing lines (see table, right). Construction costs are just part of the story, 60% of the overall project costs come from non-construction related activities such as project overheads and land compensation. But the biggest argument is that the money could have been better spent elsewhere. An alternative known as Rail Package 2 was designed last year as a test scheme for HS2 and would involve upgrading the existing West Coast mainline to allow for more trains and extra carriages. Critics point out that Rail Package 2, which was expected to come in at £8.9bn, would be less costly than the current plans.

Chris Stokes is a rail consultant and former chief executive of the Strategic Rail Authority. He says: “Rail Package 2 would cost far less but still provide a sizeable pipeline of work for the construction industry. Alongside that they could electrify the whole rail network in the North, which would take a good slug of capital expenditure and provide more opportunities for construction.”

But the Department for Transport has always insisted that this package would not be a viable alternative to a new high speed rail network, arguing it provides far less new capacity - one of the most crucial reasons for HS2’s implementation from a passenger perspective - and adding that it “provides the largest increases in capacity at off-peak times when they are less needed.”

And Hammond makes clear that the government is committed to invest in HS2 despite the need to reduce the budget deficit as he believes costs should not be the determining factor for or against HS2, or any other public project. He famously stated last year that “if we used financial accounting, we would build nothing”.

Then there is local opposition and environmental concerns about HS2. Groups opposing the scheme have sprung up all along the government’s proposed Y-shaped route. Just last month, in a bizarre series of protests, anti-HS2 groups lit small bonfires in David Cameron’s Whitney constituency. The crux of their argument is that, if built, HS2 would spoil views of the Chiltern hills, an area of outstanding natural beauty.

Joe Rukin, co-founder of national campaign Stop HS2, says: “We are against HS2 on economic and environmental grounds. There is no business case for HS2. The government is basing its case upon grossly inflated passenger projections. To spend billions of pounds on a narrow corridor serving a small, elite group of people is outrageous. We know costs will rise too because those figures are indexed upon 2009 third quarter costs. It’s nothing more than a fast train for fat cats.”

And yet there is a clear need to invest in trains. In 2010, the number of rail commuters rose to record new levels, with more passengers being carried in a peacetime year than at any time since the twenties. Figures published by the Association of Train Operating Companies show that 1.32 billion passengers journeys were made last year - up 6.9% when compared with 2009 and 37% when compared with 2000, and up a further 5% in the first three months of this year.

A Department for Transport spokesperson says: “Demand for long-distance rail travel has been growing for more than a decade and we are confident our assumptions for passenger numbers are robust.”

So will the critics be won over? The government has pledged to spend £2m planting trees along sections of the route to mitigate the visual impact of HS2. And Mark Prior, head of rail at EC Harris, has some other ideas about how government can strengthen the case for the project. The first is to include a Heathrow stop on the line (see map below). Although government views the Heathrow stopover as a crucial element of the plan, HS2 Ltd rejected the idea in its proposals, as it failed to find a business case for a major rail hub at the airport. The stopover is unlikely to be built during the first phase of the plan but has been mooted for the second phase. “Obviously we are supportive of the HS2 project in principle,” says Prior. “But a stop at Heathrow, for example, would strengthen this case as the economic multiplier effect would be huge.”

Whatever the critics might say, there can be little denying that upgrading UK infrastructure is key to the country’s economic and social development, and to keeping up with the rest of Europe. A point that Willmott Dixon’s Owen feels strongly about. “Looking at the high speed network being developed across Europe to aid growth, I know which way our neigbours are going. With our roads becoming more congested, HS2 creates faster, more direct routes to our major cities that future generations will thank us for.”

7 Readers' comments