Does the momentous structure that defined the summer of 1851 have a place in 21st century London?

With the Olympics and Diamond Jubilee, the summer of 2012 was clearly a landmark season for London. But even last year probably couldn’t match up to another legendary summer over a century and a half ago. The Great Exhibition ran from May to October 1851 and remains the largest exhibition the world has ever seen to date. It also heralded a truly magical and momentous summer for the capital and country with over six million people attending, almost a quarter of the entire UK population at the time.

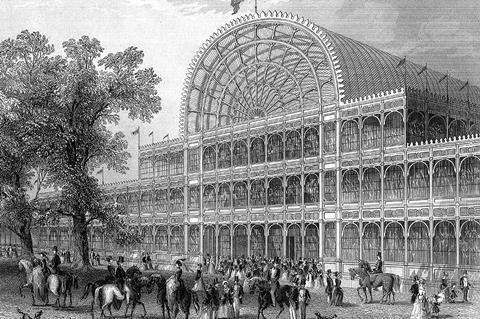

Despite its 14,000 exhibitors showcasing an astonishing array of the latest cutting-edge technologies and inventions from around the world, the star exhibit of the show was arguably Joseph Paxton’s stupendous Crystal Palace in which the event was housed.

The exhibition may have been groundbreaking but the world had never seen a building like Paxton’s before. At well over half a kilometre long and 41m high, this spectacular cast-iron structure contained over a million sq ft of glazing, more glass than had ever been used on any single previous building. The Crystal Palace was not just a venue, it powerfully symbolised the indefatigable confidence and ambition of the Victorian era.

Which is why its infamous fate was all the more tragic. In a Herculean engineering exercise almost as impressive as the structure itself, the Crystal Palace was moved from Hyde Park to its permanent south London home in 1854 after the exhibition had ended. There it stood, prompting the newly affluent park and suburb around it to flourish, until a catastrophic fire completely destroyed it in 1936. Churchill, among the thousands of Londoners who came to gaze helplessly at the inferno, was heard to mumble morosely “this is the end of an age.”

Or was it? Billionaire Chinese developer ZhongRong Holdings might have us believe not. Last month it was revealed that the organisation is in the process of finalising radical plans to build a replica of the Crystal Palace in its original reconstructed south London site which, like its predecessor, will host events and exhibitions. A planning application is expected to be submitted later this year.

So can a rebuilt Crystal Palace capture the magic of the summer of 1851 and re-establish a permanent physical legacy for both the Great Exhibition and the pioneering Victorian age from which it came?

Fantastical as the proposal sounds, this kind of venture is not exactly without precedent. London’s 2,000 year history is a violent cycle of destruction and redevelopment and scores of buildings across the capital, from Wren churches to City skyscrapers, have been painstakingly restored or rebuilt after fires and bombs. Further afield, whole cities have risen from rubble and ash pretty much as they were before; most of Dresden’s beguiling panorama of ‘historic’ buildings is in fact a forensic late twentieth-century recreation.

But even if the proposals carry historic legitimacy, is rebuilding a Victorian structure that was destroyed 77 years ago logistically, commercially or even culturally viable in 21st century London? Could Crystal Palace today, now a cosmopolitan residential suburb, really accommodate what would become one of the largest exhibition centres in the world, especially when a hard-fought masterplan for the long-delayed redevelopment of the park is already in place?

There is no compelling reason why not. Opinions will vary and planning proposals will doubtless be subject to Terminal 5 levels of opposition and delay. But a rebuilt Crystal Palace will be an inevitable draw for both tourists and exhibitors and with Earls Court about to be consigned to rubble, London will need another iconic events venue to take its place. If its replacement is to be a new Crystal Palace then rebuilding it will take no small quantity of the same ambition, tenacity and foresight required to construct its magnificent forbear 162 summers ago.

3 Readers' comments