The refurbished Savoy hotel looks a million dollars - which is just as well because it cost more than £200m to do up. Happily nobody was to blame for the cost and time overruns - except possibly the owner’s insatiably lavish tastes

After several false starts, the Savoy opens its doors to the public on Sunday, after a three-year refurbishment. It has taken nearly twice as long to do the work as originally planned and has cost more than double the original £100m budget, but once inside you know why.

The building is still recognisably the Savoy, with its distinctive mix of Edwardian and art deco style, but nearly everything is new. Instead of slavishly recreating the old decor, the building has been reconfigured to make it even more sumptuous - and bring it into the 21st century. The lifts near reception, for example, now go to the top of the building, so guests no longer have to struggle up stairs or traipse to the lift bank at the other end of the building to complete their journey.

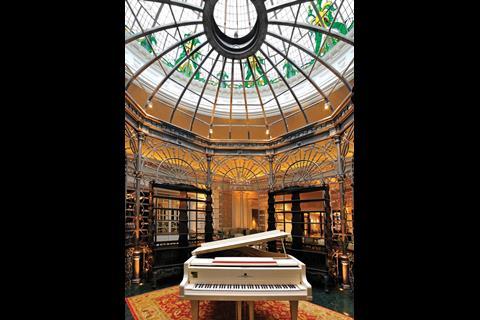

The Thames foyer, a large informal dining space at the centre of the hotel, has been brightened up with a reinstated glass cupola - the original had deteriorated and been boarded over. There’s a new gazebo beneath it, which houses a grand piano.

A bar - the Beaufort - has been created to one side of the foyer, evoking the glamour of the twenties, with black walls and golden alcoves glowing with £100,000 worth of gilt. Some front-of-house areas remain the same, including the famous art deco American bar. But it’s in the bedrooms overlooking the River Thames where the biggest changes have taken place. Previously, the only way to get a riverside view was from the bathroom. These have been moved to the back of the suites, so guests have river views from their bedrooms for the first time since 1910. Another significant change is the addition of a (reported) £10,000-a-night suite running the length of the fifth-floor river frontage.

Getting to this point has tested the patience, pockets and skills of client and project team alike. The work started in January 2008 and was originally scheduled to complete in May 2009, but when it became obvious this wasn’t going to happen, the new date of 10.10.10 was set. Main contractor Chorus was on a fixed-price contract, but the team pulled together to finish the job without a lawyer or administrator in sight. This has been helped by Prince Alwaleed, the billionaire Saudi owner, who wanted the Savoy’s opulence to match the rest of his lavish lifestyle. Also, the delays and cost overruns were nobody’s fault. The hotel was in much worse condition than anticipated, and on top of this the specification was upgraded considerably after work started.

So what is the story behind this massively expensive and time-consuming job?

There was never a doubt the Savoy needed a makeover. “I lived in the hotel for six months before work started. My son was having a shower once and half the tiles fell in on him,” says Kiaran MacDonald, the Savoy’s general manager. The services were shot to pieces and those problematic riverside bathrooms were begging for refurbishment. “The Savoy was the first hotel in London to put in ensuite bathrooms, which worked well for a few decades, but they blocked the views and the loo was separate from the bathroom, which our discerning clients didn’t like,” says MacDonald. He adds that the only thing that kept the Savoy going was its reputation.

Although surveys had already been done, it wasn’t until the hotel closed in December 2007 that it became apparent how bad things really were. “When you are talking about a building of this age there is only so much investigative work you can do while guests are in the rooms,” says MacDonald. “We found things were in far worse condition than expected, especially the services.”

The original plan had been to retain a lot of the plant, which had been installed during the eighties and nineties, but the team found it wasn’t worth renewing. Also, the hotel had never been fully air-conditioned, so the services needed extending. But installing new services proved disruptive and was a big contributor to the cost overruns. “You don’t just take out an old pipe and thread a new one in - you have to rip walls down,” says Andrew Heaver, Chorus’ managing director.

Another problem was the asbestos, which was present in greater quantities than the initial surveys had suggested.

But a bigger consumer of time and money was the installation of a full sprinkler system. According to Heaver, this was the first variation to be ordered after the job

had started.

The Savoy is an enormous building and, says Mark Iori, Chorus’ construction manager, it could easily swallow the 1,000 workers employed at the peak of the job. “You can’t appreciate how big it is until you walk around it,” he says. “You’d frequently hear people saying, ’I found another room today’.” The sheer scale of the building meant that feeding pipework through to every single room was an expensive and time-consuming job.

There were other surprises in store as the job progressed. The team found that many of the internal walls in the northern block of the building were built using Norfolk reed, a type of thatch, as a reinforcing material. “These were analysed to see if they could be retained, but unsurprisingly many of the walls weren’t stable and had to be rebuilt,” says Iori.

One of the reasons why the team didn’t fall out was because they were always honest about the problems. Iori says there was “cause for alarm” right at the start of the job, after the investigative work. Regular meetings to discuss the issues were essential to keep the job from going off the rails. “We were part of the team from day one,” says Heaver. “The client embraced what we said, and there were difficult moments, but nobody fell out. We were in a position to sign up to something deliverable and realign the project with new opening dates.”

Bizarrely, the biggest and most risky part of the job went without a hitch. Moving the bathrooms from the front to the back of the bedrooms was far more complicated than reconfiguring a few plasterboard partitions. To understand why involves a short history lesson, because when the hotel was completed in 1890 it didn’t have ensuite bathrooms. The Savoy’s owners realised this was going to be an important drawback in a luxury hotel so opted for a radical solution.

Originally the suites overlooking the river had balconies. In 1910 a new facade was built on the edge of those by inserting a series of 1.2m-deep beams at roof level. These cantilevered over the edge of the original facade and were used to suspend the new one. The space between the two facades was used to create the new bathrooms, which meant they were blocking the river views.

Reconfiguring the river suites meant that the original, heavy masonry facade inside the rooms had to be demolished. This was made more complicated because the facade also supported the cantilevered beams from which the 1910 facade was suspended. The only way to do this was to install temporary works on either side of the inner facade to support the roof beams. With these in place the loads were transferred to the temporary works and the masonry walls were demolished. With the wall out if the way, a steel frame with slender columns was constructed, ready to support the roof beams, and then the loads were transferred to it from the temporary works. “The external facade is terracotta, which is

fragile and unforgiving,” says Jim Solomon, Buro Happold’s engineer on the job. “We had to be careful not to damage that facade when transferring the loads on to the temporary works and off again to the new structure, which meant a lot of monitoring.”

The other big reason for the time and cost overruns was simply that the third phase of the job ended up being much grander in scope than originally planned. This part of the job included all the front and back-of-house areas, and was based on provisional sums when originally tendered, so it’s no surprise a grander specification has ended up costing more and taking longer.

At the end of last year, when the final 10.10.10 date was decided on, Chorus threw everything at the job. The team worked over Christmas and has since worked 24 hours a day, seven days a week, with 200 people regularly working nights. Armies of fibrous plaster specialists repaired and recreated miles of plasterwork, and 300 top decorators sanded, painted, grained and marbled acres of woodwork, columns, ceilings and walls. At the end of August, Chorus handed the building over to the Savoy so it could furnish the building and train up staff ready for the opening date.

Did Heaver ever worry that this would be the last job Chorus would do? “It has been a rollercoaster ride throughout the job, so that thought never really crossed my mind. We hadn’t done anything wrong, and luckily the client had the cash to carry on,” he says. “These sorts of jobs only come up once in a lifetime, so I don’t think we will get another one of these.”

![Hassell - Brighton Business School[1]](https://d3sux4fmh2nu8u.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/7/4/1/1886741_hassellbrightonbusinessschool1_568688.jpg)

No comments yet