Contractors find themselves between a rock and a hard place - the rock is the relentless rise of raw materials; the hard place is feeble demand and low margins. But is there anything they can do about it?

The worst kind of problem is one with no obvious solution. And, unfortunately for the construction industry, rising materials prices falls into that troublesome category. Over the coming months the cost of raw materials is set to soar, and nothing can be done to prevent it. The threat has been looming, spectre-like, over the industry for more than a year now as prices have been steadily increasing, squeezing the profit margins of businesses doing work at prices agreed when costs were at rock bottom.

The two main headaches are the price of iron ore, a key component of steel, and the price of copper. In the past two years, the copper price has risen 275% from its low point at the height of the credit crunch and is now trading near its all-time high, while the iron ore price has virtually doubled to $1.82 per metric tonne since last summer. The adverse effects of these price increases have ricocheted through the industry causing havoc with tender price forecasts for cost consultants and estimators (see “Estimators speak out”, opposite). All of this puts main, and particularly small to medium-sized contractors, in a dangerous position as they are forced to gamble on future cost moves. If they make the wrong call it could threaten their survival. As Rick Willmott, Willmott Dixon chief executive, told Building last month: “Prices are at rock bottom and there is only one way for them to go next: skywards. And quickly. This will push contractors into their recession for the next five years or so.”

Here we investigate the economic forces behind the rising materials prices, the effect this will have from estimating through to tendering and delivering schemes, and how firms can best position themselves.

It’s all about China

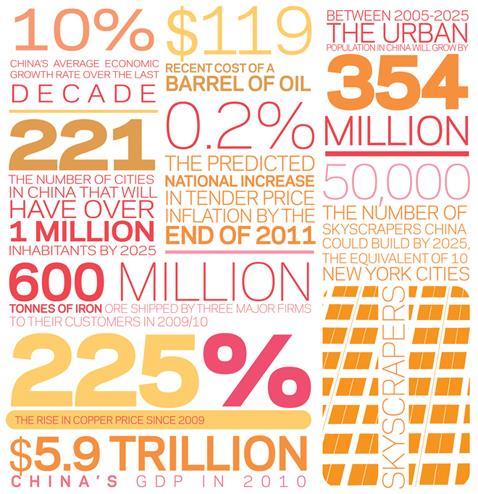

The driving force behind the inflation in raw materials is the insatiable demand from China. The country is expected to have 221 cities with more than a million inhabitants by 2025, compared with just 35 in the whole of Europe. Its urban population will have virtually doubled to almost a billion people between 2005 and 2025. To house all these people it could build up to 50,000 skyscrapers, the equivalent of 10 New Yorks. This demand means massive quantities of materials are bound to China, leading to scarce supplies elsewhere and higher prices. And the strength of the Chinese economy and the financial power of its firms means they can out-compete global rivals when it comes to sourcing materials.

How bad could it get?

The threat posed by rising materials costs in the UK is not to be underestimated. Noble Francis, Construction Products Association’s economics director, says: “Falling demand across the industry and sharp rises in costs during 2010, such as the 46% price increase in copper and 80% in iron ore, are exacerbating problems for the industry.”

The fear is that jobs which were priced to make a certain level of profit will suddenly become unprofitable as costs increase above the forecast level: “Commodity price rises are creating real problems for the industry,” says Paul Moore, head of cost research at EC Harris. “Contractors are now being faced with the problem of delivering schemes which were won at excessively low prices.

“In this situation, in new tenders, clients and/or contractors may be choosing to exclude some items of commodity price risk. Where contractors have pressurised their subcontractors and cut their profit margins to the bone to secure workload, rapid increases in costs could mean that contractors find themselves caught out with limited options to recoup their losses.”

This means some contractors are putting clauses into contracts in which future increases in commodities are shared between them and the client.

Preparing for the storm

In the face of this inevitable increase in materials costs and the expected hit to margins, exactly what can UK-based firms do to reduce the impact?

First, they can try to pass on materials price increases to their clients. This hasn’t been happening very often as competition for work is too fierce, but it needs to be addressed. Graham Davey, director of procurement at VolkerFitzpatrick, says: “We do expect further increases in materials prices this year as a result of higher commodities and raw material costs working their way into the supply chain, some of which are 20% higher than last year. Margins are being squeezed as a result.

“To counter this we must work smarter on site; working with our clients and our supply chain to reduce our costs through efficient programming, adapting work practices, utilising pre-fabrication methods and getting the quality right first time. It is inevitable however, that some increases will filter through to clients and end users at some stage in the future.”

Some firms are tackling these cost pressures head on. “We are coming under cost pressure on materials such as copper, steel and fuel but to offset this, we have been cutting costs, such as payment processing costs, in other parts of our business,” says Simon Carr, managing director of Henry Boot Construction.

“Rising costs are a concern because we can’t see tender prices increasing for another 18 months. There’s no way the industry can carry on like this and when tender prices do start to rise, it’s likely to be in the double digits. Multidisciplinary firms like ours can offset pressures in one market with opportunities in other markets but not all firms can do that”, he adds.

Sarah Davidson, head of corporate research and development at Gleeds, says: “Other firms are closing loopholes in contracts and being incredibly specific in their tenders as to which products they will use. Tenders are now very heavily qualified.” This gives the contractor a clear idea of the potential costs it will face and can make for accurate tendering.

Rising materials prices are a real problem for contractors and while there are some ways to offset the effects of higher prices, many of these are just temporary. There needs to be a change in the attitudes of clients in the sector and they need to appreciate that if construction firms can’t recover their costs, they could go out of business.

Ken Gillespie, managing director of Galliford Try’s construction business, isn’t willing to take price increases on the chin. “Right now there are some frightening trends in materials prices. We have tried to reflect this in our bidding for contracts and have said we are not prepared to fix the materials price element on bids. This means that some clients put our tender straight in the bin but we will not change our stance on this.”

For the industry to operate profitably in such an environment, more contractors need to take a similar view.

Iron Ore

The iron ore trade is dominated by just three companies: Anglo Australian firms Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton and Brazilian giant, Vale. Between them, these firms shipped more than 600 million tonnes of iron ore to their customers in their most recent financial years.

Demand for iron ore has been increasing for years as it is a key component in the steel manufacturing process. China has been a massive source of demand as its population urbanises and steel is used for structures in buildings, rail networks and its increasingly hi-tech industrial production and manufacturing processes.

The bulk of the iron ore heading to China comes from the Australian desert. The Pilbara region, in North-Western Australia, where BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto have their operations, is ideally placed for quick deliveries to the Chinese steel mills on its southern coast.

Copper

China is, again, the driving force behind record copper prices, which have recovered after collapsing during the global financial crisis. Copper is used for pipework and electrical wires within buildings, but also on the countries expanding electrical rail networks. But while strong demand has played a part in the rising copper price, other factors have also been at play.

Natural disasters, such as earthquakes in Chile, the world’s biggest copper producing nation, have halted production at a number of mines. And many mines still in production have begun to extract less copper.

The copper that was easy to extract has already been picked and what is left in large deposits is more difficult, and more expensive, to get hold of.

Oil

The oil price has an impact on costs as diverse as fuel, plastics and chemicals. Supplies can be increased or reduced virtually at will by large producers, such as the members of OPEC, the oil production cartel. But it is in their interests for oil prices to remain high, albeit at a level which does not severely affect demand.

Finding and extracting oil is becoming increasingly difficult. Firms have been searching for oil in deep water, in cold climates or in countries where there is political instability in an attempt to find an alternative to the oil they extract on a daily basis.

At some point, which may already have been passed, more oil will have been extracted than remains that is commercially or technically recoverable. This is called peak oil and it has been in focus this month - cables revealed by Wikileaks showed US concerns that Saudi Arabia has overstated its reserves. If this is the case, the oil price, which recently soared towards $120 per barrel, could spiral out of control.

Political unrest in the Middle East has pushed up oil prices as uncertainty in one of the world’s biggest oil producing regions increases the threat of disruptions to supplies. Although oil prices were already increasing thanks to global supply issues, analysts in the Gulf forecast last month that in a worst case scenario, oil prices could virtually double and hit $220 per barrel.

Tender price gamble: estimators speak out

Sarah Davidson, head of corporate research and development at Gleeds

Rising prices and unwillingness from some companies to tender for jobs are causing havoc with tender price forecasts. These trends are making life tough for those who have to second guess the market in a time of uncertainty. At present it’s very difficult to forecast tender prices. It’s different across the UK but we are seeing a reluctance to tender in London and the South-east from some companies. Those that have lost staff do not see enough certainty to re-hire and they do not want to promise more than they can deliver while costs are increasing.

The market is still very nervous and steel price increases, which will come through in the next few months, don’t help. Margins will probably fall as competition for most contracts is still fierce. Contractors need to recover their higher costs but in this market it is very tough.

Simon Raine, head of commercial services and director at Faithful + Gould

The laws of supply and demand will offset the increase in the prices of raw materials and energy resulting in a broadly flat market in 2011. The commercial market is not yet ready to fill the gap left by the sharp reduction in public sector construction which will lead to continuing aggressive tendering.

Main contractors’ preliminary results have already fallen to a level that it is questionable whether sufficient management time is provided to properly manage projects. The inevitable consequence will be more projects running into cost and programme difficulties. But there is capacity for further reductions from those subcontractors that are required later in the project programme, such as services and lifts, who have yet to feel the full effects of the recent steep reduction in demand. While Tata, the owners of Corus, has announced price increases in steel from January 2011, it remains to be seen whether this can be sustained in the face of competition. Previous experience indicates that this is doubtful. Faithful + Gould expect inflation to return in 2012 and 2013 as demand picks up and are predicting 3% for each year.

This will prove a difficult period for contractors trying to match a reduced capacity in the construction market with winning work in

what will still be an extremely competitive marketplace.

No comments yet